|

By: Eleanor Lin (CC '24) On November 20, the Columbia Science Review hosted a panel discussion featuring three prominent science communicators: Dr. Esther Choo, Tyus Williams, and Dr. Rose Marie Leslie. Panelists fielded questions on how they are harnessing the social media platforms Twitter and TikTok to shape the dissemination and discussion of science. The panel was co-moderated by CSR OCM's Savvy Vaughan-Wasser (CC '22) and Everett McArthur (CC '23). Panelists

Co-ModeratorsSavvy Vaughan-Wasser is a junior in Columbia College ('22) majoring in Neuroscience and Behavior. Her love of animals and psychiatry is guiding her to become a doctor, with a possible intersection between animal and human medicine. Savvy has experience in a research lab studying cancer, as part of a research team geared towards fostering resilience and inclusivity for non-binary students in all-girls schools, and volunteering at animal hospitals. She enjoys archery, dancing, and anything chocolate. Everett D. McArthur is a sophomore in Columbia College ('23) planning to major in astrophysics. Currently, he’s involved in galactic dynamics research. In his free time he does public lectures in his hometown. He hopes that his efforts will increase scientific understanding in his community, as well as increase diversity in science. He enjoys long hikes, art, and playing the piano.

0 Comments

By: Hannah Lin (CC '23)

By: Hannah Lin (CC '23)

You’re an infectious disease ecologist in the field of environmental health sciences. That isn’t your typical biologist or chemist. Could you explain what your title means, and also what your personal and professional path to this field looked like? As you mentioned, I’m an infectious disease ecologist, and there are only several hundred of us in the world. Those of us that identify as infectious disease ecologists are people who typically have PhDs in ecology or evolutionary biology, oftentimes also applied mathematics, and who essentially study infectious diseases from the lens of ecology and evolutionary biology. You can think of infectious diseases as predators, except they have much smaller bodies than their prey. So many of the same types of population level principles that have been used for fifty, eighty years now to investigate predator-prey relationships have now been applied to infectious diseases. Much of the same mathematics that’s used in, say, fisheries biology or predator-prey population dynamics, we apply that to infections.

That’s kind of the framing of the science. We also use evolutionary biology to study either the biology of the host, which is what my lab does in our approach to the immune system, or also the evolution of pathogens themselves. Many disease ecologists also look at the evolution of things like flu and HIV through the lens of natural selection, which is something all species experience, particularly looking at it from the disease angle. So that’s disease ecology as a field. In general, I’ve always been an ecologist. Well actually, I first started out in a genetics lab doing more evolutionary work with fruit flies. Then I moved to doing field work and endangered species work with Arctic seals, so I was working on the endangered species listing for ringed seals, which are the primary prey of polar bears (when you see pictures of a polar bear pouncing on seals, it’s those seals I used to work on). Because I was studying both mathematics and biology, I wanted to be in an area that was very mathematically leaning. In ecology, the two areas in which there is a lot of modeling applied are infectious disease work and fisheries work. I went the infectious disease route so I could use my math skills. From there, I just got really interested in working on childhood infectious diseases, did my whole PhD on polio and measles, then subsequently did work on other childhood and early life infections like chickenpox, and also worked on Zika for a bit once Zika emerged.

The last several years, my lab has also been funded to see if we have seasonal changes in our immune system that influence when we get sick and if the basis of this is a seasonal biological clock. That’s the other area of my research. I think that type of work makes a lot clearer the types of things I study as a disease ecologist. From my perspective and just in general, humans are just another mammal, so we can ask the question: how does the fact that we’re just another mammal play into our health and wellbeing? Jumping into your COVID-19 related research now, from what I saw, you and your team have been studying the immunology and transmission of this pandemic. Could you talk about your work thus far? In terms of COVID, my work has fallen into three distinct projects. One of them, which I would say is most closely aligned with the other work in my lab right now, is looking at the immune system during COVID. It’s quite clear that it’s the immune system that is doing the majority of the damage in individuals who are hospitalized, severely ill, and may succumb to the infection. For some individuals, what happens is the immune system is over-reactive and has an incredibly inflammatory immune response. Our immune system has the ability to react very strongly to an infection, but we also have processes in our immune system that keep it in check, that harness it in and don’t let it get too bonkers. But on occasion, what happens is those regulatory processes that would usually manage your immune system can fall apart for many reasons, which for COVID-19 seems to be the case. The inflammatory response just spirals out of control to such an extent that individuals can get what we call immunopathology, where you have pathology, or harm, that is being done to your body by your immune system, including things like tissue damage in the lungs, which can make people have ARDS (acute respiratory distress syndrome) and be put on a ventilator.

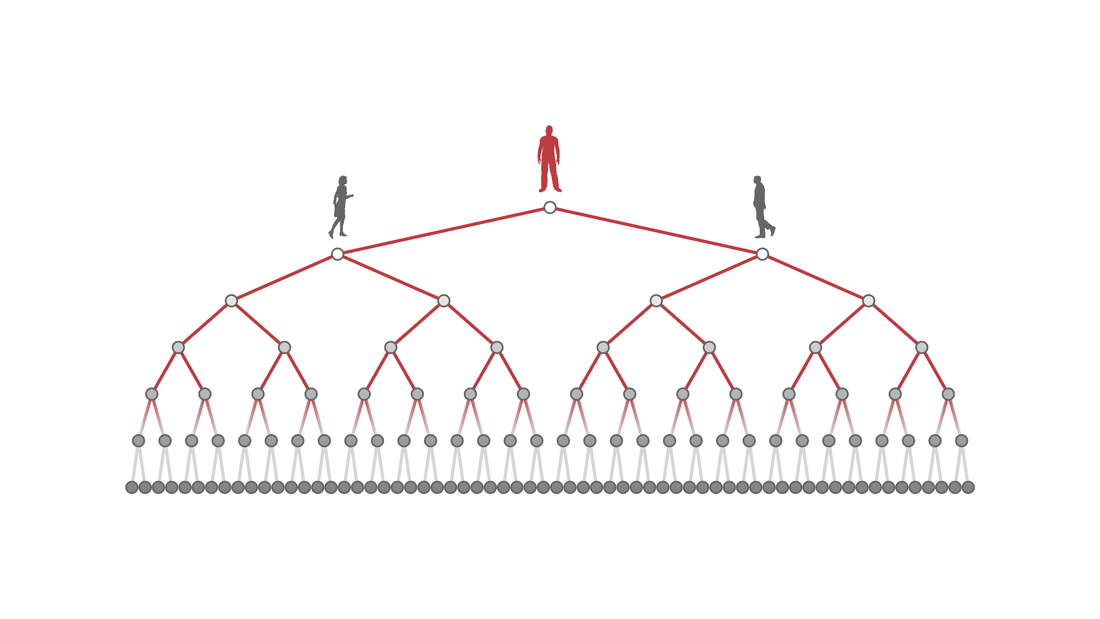

Our hope is that now by scouring the literature, by integrating data from different sources, and by digitizing data that become available (and now we’ll be using clinical data from Mt. Sinai and Columbia), we can come up with predictors for markers of our immune system that are predictive of what path the person will follow. If someone ends up in the hospital and you take a blood sample from them, we would like to be able to predict with some probability, what the chance is that this person is going to be, say, hospitalized for a week or two, recover, and be discharged versus need to be put on a mechanical ventilator and either go down the path of continued tissue damage and potentially death. As of right now, all of those paths are just dictated by your immune system. There’s not much that is able to be done on the care side of things to dictate people’s pathways that they take. Ventilators are just trying to minimize the amount of tissue damage that’s being done by helping the body supply oxygen, but they are not actually helping heal. The whole process of healing is a process of the immune system as well. The second project I have going on is transmission modeling for New York City. There are lots and lots of modeling groups worldwide that have been constructing transmission models for COVID. Where my group differs from some of those other groups is in two areas.

analyses for all these unknowns for the immune system and what’s going to happen. We need to model into the future and say, okay, if our immunity works this way, then this wouldn’t happen. If our immune system works this way, then this scenario would happen. It’s kind of like when you think about climate change scenarios: if we cut down carbon emissions this amount, then we project this will happen. Same kind of deal, but for the immune system.

Also, I’ve been working with the air pollution scientists in my department to come up with a way to measure social distancing and the slowing down of cities on lockdowns. You can easily come up with a policy; for example, the governor’s policy for lockdown in New York State where people were told to stay home. But to actually quantify and measure that is really hard unless you have something like proprietary cell phone data from every person and you can see where they’re going.

have access to. We’ve been generating algorithms that will go and take snapshots of Google Maps for every neighborhood in the city, and then puzzle-piecing those together to see how much movement there is around the city on fifteen minute intervals, going from pre-pandemic to now. We know via this type of publicly available data mining how much movement there is around the city, which can, in some ways, be a proxy for transmission potential.

My last COVID project is work that is under review right now and should be published shortly that looks at the socioeconomic and racial disparities in social distancing. When we look at the disparities based on race and ethnicity for COVID-19, there are essentially two sides of it. There’s first, thinking about what the probability is that an individual acquires the infection, and that's going to be largely dependent on how much infection is in their community, their ability to socially distance depending on what type of work they do, and also housing: if they live in a multigenerational household or if they live in a household where, if an individual is infected, they can stay away from other household members and quarantine effectively, that type of thing. So there’s that transmission side of it.

race/ethnicity, percent of essential workers, median income, and you can also get things like education, all of these things are very tightly correlated within New York City and, I would say, more broadly in the United States. If you’re poor, you’re more likely to be Black or Brown. If you’re poor, you’re also more likely to be a lower-wage worker that has to leave the home in order to work. You don’t have the luxury of staying home. All of these things come together to shape, at a community level, how much transmission there is in the community and at an individual level the risk that people face.

higher subway use during the pandemic also had higher incidence of cases, and we believe this is because of community transmission because of the social distancing inequity that's faced.

What are the broader goals of your research? Do you want to provide models for policymakers when reopening cities or something else? This is one thing that is really interesting. For instance, using the models that we’ll have for New York: inevitably, yes, policymakers are going to pay attention to that, but I’m not really in the business of modeling for policy. I’m much more in the business of modeling to understand fundamental biological processes with the aim that understanding the underlying biology will then inform translational medicine and policy. In reality, the type of work that I do, since it is more biology focused, is not meant for rapid action. If I were wanting to inform policy very directly, then I would be doing different types of modeling: for instance, modeling what the optimal criteria for shutdown and reopening would be or if you wanted to do cocooning for at-risk individuals, how you would stratify populations so some people would stay home, some would go to work, that kind of thing. Those are very directly applicable policy things, whereas my work is much more long-horizon, informing biology. As you said earlier, prior to COVID-19, you were researching other infectious diseases like polio and measles. How was the transition from researching those to this current pandemic, and did your experience with those give you unique insights into COVID-19? Yeah, definitely. The thing is that I’ve been working on the biology of acute infections for so long and coming at them from a biological angle, so it’s not all that different. COVID is just another directly transmitted infection. There is a playbook for infectious diseases. Like I was saying with predators and prey, infectious disease systems behave a certain way. There are biological bounds to how they behave.

I think I can say now that I’m the world’s expert on the seasonality of infectious diseases - that and seasonal clocks, biological rhythms in humans, are the two things that no one ever studied. Before COVID, there were so few people in the world that had any interest in seasonality of infections, and even fewer people who had ever done real empirical research in that area. When COVID hit and you had things like Donald Trump saying, “it’s going away as soon as it gets to summertime,” it was like every reporter was emailing me. I think I was uniquely placed even compared to my close colleagues because I realized I had spent so many years thinking about it that I just very innately know the nature of seasonal disease dynamics, and the math behind it is very ingrained in my brain. I noticed it with my colleagues when I thought they had the same skill set as me, but because they hadn’t specifically worked on that one area, they weren’t as well placed to think about that for this new infection. I would say my seasonality work made it so that as soon as people were asking if it was going to go away in the summer (I even had some other disease people who I would hear have that hope), I was like, no, you guys, no! I think I had just thought about that problem for a lot longer than other people had. Is there a reason why biological rhythms and seasonality haven’t really been extensively studied?

pace, getting papers out, getting grants, and such, there’s no incentive for anyone to spend their career on that unless they’re just really intellectually driven by it, which is why I worked on it.

For infectious diseases, the seasonality is very, very obvious in any infectious disease data that you look at. I would think that one of the reasons that people hadn’t studied it could just be that people don’t look at ubiquitous things, maybe? When something is so common, people don’t realize that it’s very interesting: it’s just like, the earth rotates around the sun and is tilted on its axis, so of course we have seasons! I think it’s one of those things that, since it’s so common, it gets overlooked. Lastly, what is your perspective on the future, and for a note of optimism, what gives you hope for the future? I’ll give you the good and the bad. My perspective overall is that with global climate change and the widespread destruction of natural ecosystems, including land use change and deforestation, humans, especially over the last 200-300 years, have done what is pretty close to irreversible damage to our planet. If I were just to say very bluntly, I think this pandemic has been a slap in the face from the earth to human beings. Humans have notoriously been going into natural spaces for so long where we don’t really have any business to be in. It includes forcing novel contacts with species that we usually don’t interact with. In the past, this has posed problems for us, like having zoonotic diseases that have moved into humans - things like all of our flu viruses, Ebola, HIV. But I think that in the past, there have been very few things that have just gone straight from jumping into humans right to a pandemic. Also, some of the past emergences were either more localized or they happened during a time when we didn’t have such widespread global connectedness, in terms of social media, news. Now, all of a sudden, it’s an age-old problem (age-old meaning industrial age-old): humans going places we shouldn’t be, we have a spillover from hosts into humans, and now we have this pandemic. But everyone is aware of it now, and there have been huge economic consequences and loss of life in a very short amount of time.

I think that this is going to be a turning point where either, optimistically, people realize we need to be stewards of our environment and pay attention to these things, that our actions have consequences, and therefore become those stewards that we should be, tackle climate change, tackle land use change, think about widespread extinction and pollution of our environment. And if COVID doesn’t do that, I really don't think anything else will. There’s really not much more of an acute shock that you can have from the environment onto humans than this. So I do think it does have the potential to be a turning point, but we’ll see. Studying Psychological Distress in NYC Healthcare Workers During COVID-19 With Marwah Abdalla7/24/2020

By: Hannah Lin (CC '23)

Can you introduce yourself, your titles and affiliations, and talk a bit about generally what work you do? My name is Dr. Marwah Abdalla. I’m an Assistant Professor of Medicine in the Division of Cardiology, I’m a clinical cardiologist and a clinical researcher. My areas of expertise include critical care cardiology, and I’m the director of education here in the cardiac intensive care unit. With regards to my research expertise, I work in hypertension and sleep. Shifting now to your work regarding COVID-19, you were the leader of a study which characterized psychological distress and coping among New York City healthcare workers during the peak of the pandemic, the largest such study done in the US. Could you talk about when and why you decided to research this? This all came out from my experiences taking care of patients during the pandemic. I had the privilege of serendipitously being in the cardiac intensive care unit as the attending during the first week of the pandemic when it hit New York and when the very first case came through the doors of New York Presbyterian. So it was an interesting and serendipitous opportunity where everything came together very, very quickly with regards to what the questions were that needed to be answered. You can imagine that during the first week of the COVID surge, there were so many unanswered questions. There was also a lot of uncertainty amongst family members, patients, and the staff as to what this new pandemic meant.

That’s really where the idea came from: the observations on the ground during the very first week of the pandemic and saying, “This is going to be here for a really long time. How can we help not just our patients but also really ground ourselves and be helpful to our colleagues who are taking care of those patients?” Just running through some statistics from the paper, fifty-seven percent of participants screened positive for acute stress, 48% screened positive for depressive symptoms, 74% had concerns of transmitting COVID-19 to family, and 80% reported engaging in at least one type of coping behavior, with physical activity being the most common. Were there any responses you got that surprised you, or were they relatively close to what you expected? I think this paper and the data definitely highlighted what our hypothesis was going to be, that there were going to be a lot of people who had acute stress syndrome and fears about transmission. At that point in time, in early April, when we launched the study, there were still questions about N95s and whether people should be masked or not masked that were part of a national conversation. There was a lot of fear about transmission, and a few colleagues who were frontline healthcare workers actually got sick, and some, unfortunately, passed away subsequently from that. The national discourse was about that, so I think that was not surprising.

really remarkable and it goes to show how much healthcare workers, even in the midst of a crisis, are finding new meaning and thinking about how they can collectively work together to beat this pandemic. So many people were collaborating and trying to think quickly and change in such a way that was really refreshing.

In the paper, it says participants were given the choice to enter a longitudinal follow-up for up to 3 months. Could you talk about your progress on that? Our participants are still part of the study and we'll be completing it soon. The last participants are finalizing their study responses. We have not yet analyzed that portion of the data, where our goal is to understand what the long term effects of the pandemic are on our healthcare workers who were so gracious to fill out the first portion of the survey. Do our participants continue having acute stress months out, is it limited to just the peak of the pandemic and things get better, or is it that people are still struggling while other things pop up as the months go by? I think that’s an important thing to understand as we figure out how we best support healthcare workers during any sort of public health crisis, but particularly for COVID-19, since it’s still an ongoing international crisis. We need to prepare ourselves to help others who may be going through the pandemic and say, “This is what you may expect in your own healthcare workers.” I think those are important conversations to be had. Obviously, our study results are limited to our New York campus, but I think there are elements that are probably shared since it’s an international pandemic. In China, a study showed that healthcare workers during COVID-19 actually do have signs of psychological distress, and we don’t know how far this distress stays with individuals. The paper also says that your findings highlight the need for rapid interventions to reduce psychological distress in healthcare workers. Have you seen any of those rapid interventions put into action? Actually, while we were launching the study, what was great was that both Columbia University and NewYork Presbyterian implemented wellness resources for healthcare workers. All our participants had access to wellness resources during the study because we thought it would be unethical to just collect information. It’s been great that on campus, there’s been an understanding of the fact that healthcare workers during a pandemic need this extra support. What we’re really trying to highlight is that for other institutions and organizations for which there may not be access to the same resources that our healthcare workers had, they might want to consider having this in place. We want healthy healthcare workers; the wellbeing of healthcare workers have to be at the forefront of organizations that are going through the pandemic.

I think for students who are interested in medicine and public health, and especially research, keep asking questions, learning as much as you can, and really try to spend time in clinical spaces if possible. There’s a difference between learning medicine versus practicing medicine, and for me, what was always inspiring and rejuvenating was being able to be with patients and having that opportunity to interact with healthcare workers, nurses, advanced practice providers, attendings, the whole gamut of healthcare. That was really motivating while going through my own journey and learning as much as possible. I always like to end with some optimism: what gives you hope for the future? It was really humbling to see over the past couple of months how quickly the world came together to try to beat and find solutions for COVID-19. There continues to be hope, especially in the scientific community and the public health community, that we can come together and figure out how we can move forward to combat COVID-19. That gives me a lot of hope. Public Health Messaging in Minority Communities and COVID-19’s Neurological Effects With Hiral Shah7/22/2020

By: Hannah Lin (CC '23)

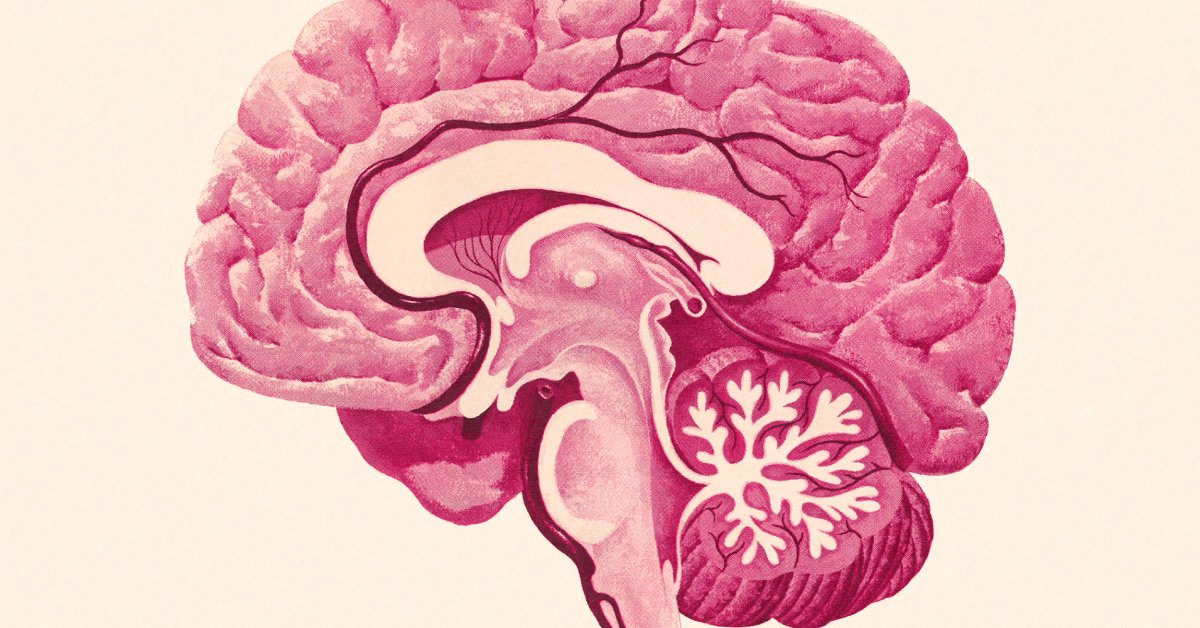

Could you talk a bit about the work that you do? I work in the Department of Neurology and in the Division of Movement Disorders, so I mostly focus on seeing patients who have degenerative diseases such as Parkinson’s Disease, Huntington’s Disease, and others. My research focus is centered around public health approaches to improving access and treatment for neurological disorders. In that capacity, I also work as a consultant for the World Health Organization. How did you get started in public health research and neurology?

little serendipitous that I had the opportunity during my training to work at the World Health Organization and really observe firsthand how public health initiatives can transform care delivery in a variety of ways.

From what I saw, your COVID-related research focuses on health disparities for Black and African American New Yorkers. Could you talk a bit about that? Here in New York, the initial epicenter of the COVID-19 pandemic, we observed firsthand the egregious health disparities which were further highlighted in the context of the pandemic. Though we suspect that social determinants of health and a multitude of factors such as issues related to education, housing, insurance, health literacy, and structural racism all have played into the more severe outcomes and the brunt of the burden of the illness being borne by our minority communities, I still think that there is a lot left to be learned in terms of what the modifiable risk factors or modifiable barriers are that, as clinicians or as public health experts, we could try to leverage to improve our response to the pandemic, both now and in the future.

and related myths surrounding the disease that could shed some light on ways that we could improve the health of these communities.

How is your progress on these surveys? Are you still collecting responses?

Where do you see your research going in the near and far future? I know you talked about the broader goals of having your work reflected in public policy as well as community and institution-level strategies. I think in the near term, within our department, we may be able to modify our messaging and the way that we educate the public in terms of safety and coming back to the medical center. In the era of the COVID-19 pandemic, we’ve also observed that many are reluctant to come seek routine care because of fears related to COVID, so I think if we can better understand what those fears are, which is part of the survey, then we can better address those concerns to ensure that there aren’t unnecessary delays to care that further cause negative health consequences for our communities. In the long term, I think that we simply don’t know enough about the effective strategies to reach minority communities. Sometimes, simply translation of messaging is used to communicate with Hispanic communities, but I think that we need to think more creatively and out of the box in terms of how we get these public health messages out to the community, whether it means relying on local faith leaders that are based in the community or using mass media or alternative approaches. I think we need to think outside of the box in the future because clearly, public health messaging has been a little inconsistent throughout the pandemic, which has led to more confusion for the public on how to respond and what guidelines to follow. I think we need to think of novel ways to reach minority communities and provide messaging that’s a little more tailored and culturally appropriate. Switching gears to your clinical work: obviously, you not only do research, you’re a neurologist as well. Could you talk about your experience as a neurologist during the pandemic?

challenges with using the technology and positioning themselves to allow for an appropriate examination. And, many of our patients are older adults; I think we all know family members or friends ourselves who struggle with these new technologies and how to implement them. So though I believe it’s been an exciting time in which we’ve been able to take advantage of and leverage telemedicine and information technologies, I think it’s also exposed a lot of the barriers to its implementation universally.

In terms of COVID-19 infection, we’ve heard a lot about the respiratory and cardiac effects. Could you talk about the neurological effects? Absolutely. The neurological manifestations of COVID-19 have been of great interest. I think at the onset of the pandemic when it became obvious that anosmia, or lack of sense of smell, was a feature of the disease, that got a lot of people’s attention. It’s thought that the virus likely gains access or entry into the neurological system by the mucosal membrane in the nose and that maybe travels to the brain in that way, but this has not been confirmed.

For students out there who want to pursue a career in neurology or public health research, do you have any advice or life lessons you’d like to impart? I would just say follow your passions and your interests. Always look for ways that you can get involved. I think learning on the job or on the ground, so to speak, is one of the best ways to figure out whether it’s really something that interests you and something that you want to pursue as a lifelong career. I would encourage students to try to find opportunities and get involved. Both regarding science and research as well as society at large, what is your perspective on the future, and what do you want the future to look like? That’s a big question. I think that this period of time has really opened a lot of eyes for folks in terms of the egregiousness of health disparities and how that impacts some communities more than others. I just hope that it leads to more awareness and activity to try to tackle those problems, because I think that these problems have existed long before the pandemic and will continue long after. Perhaps with additional attention and interest, we can really have some more momentum to solve some of these issues, because I think if they are prioritized and recognized for the terrible consequences that result, we can all really work together to make a change and improve the health of our minority communities in particular. I think that that knowledge will translate to improving the health of our communities at large. Thanks, Hannah, for taking the time to speak to me! The Impact of COVID-19 on Transgender and Nonbinary Americans with the Project AFFIRM Team7/20/2020

By: Hannah Lin (CC '23)

Can you introduce yourselves and what work you do? RENATO BARUCCO: My name is Renato Barucco. I’m the coordinator of the LGBT health program, so I coordinate all the different projects of the program across psychiatry and nursing under the direction of Dr. Walter Bockting and Dr. Anke Ehrhardt.

people gave us a lot of information in their answers, so we thought it would be important to do a qualitative analysis of these answers. That’s what I’m doing right now.

WALTER BOCKTING: I’m Walter Bockting. I’m the principal investigator of the overall study, Project AFFIRM, a longitudinal study of transgender identity development across the lifespan. We have been following participants for over three years. It was Jeremy’s idea during this COVID time to contact them again. It wasn’t initially planned, this was a bit of an expansion. Normally, we have people come in for interviews, and they’ve done that three times: baseline, one year, and two year followup. This time, it was fitting, given the social distancing, to do an online survey instead to see how our transgender people in the three cities that Renato mentioned are coping with COVID-19. JEREMY KIDD: I’m Jeremy Kidd, he/him. I’m an addiction psychiatrist, and when I started this project, I was a postdoctoral research fellow at Columbia University and New York State Psychiatric Institute in the division of substance use disorders, but I’m now transitioning into an assistant professor role at Columbia. I’ve worked with Walter since coming to Columbia in 2013 on some sub-projects within the AFFIRM cohort, and a lot of the work that I am transitioning into doing is looking at social support and the role that social support and gender affirmation play in mitigating some of the negative health outcomes and health disparities that we know occur for trans and gender nonbinary folks.

KASEY JACKMAN: My name’s Kasey Jackman, I use he or they. I’m currently a postdoctoral research fellow at Columbia School of Nursing. I’m also a psychiatric nurse practitioner, and I practiced with the Nurse Practitioner Group at Columbia as well as in New Jersey. My role with Project AFFIRM has been from the beginning of the project, when I was a PhD student. I started in 2013, and I’ve been working with Walter since then. There have been a number of substudies and I’ve led two of the substudies. The first one was about nonsuicidal self-injury among transgender people, and then the second one, more recently, was among Latinx transgender people looking at discrimination, stress, and sleep. We collected various types of data, which was the first time we’ve done that with this cohort. We collected actigraphy data, which means monitoring sleep and wake patterns and activity levels. We collected two samples of saliva, one for cytokines, one for DNA, and we also did some blood pressure monitoring for feasibility to see if that would be something we might want to expand in future studies. In terms of the COVID-19 study, I’ve worked on formulating the survey, distributing the survey, and planning data analysis. You all come from various different backgrounds. Could you talk about your personal and professional paths to the work you’re doing now? JEREMY KIDD: I came to Columbia in 2013. I’m actually back in rural Virginia now, where I grew up, waiting on my COVID test results so I can see my family! I went to medical school in Virginia, then came to Columbia in 2013 for psychiatry residency and was fortunate enough on my interview day to meet with Walter and I think at that point, AFFIRM was probably being planned, I don’t even know if it had started yet.

community, a lot of advocacy and activism work, and I think those are the stories that I hold in my head and the relationships that I think inspired me to keep doing this work, because I recall all of the challenges and the discrimination and the things people that I really care about have experienced, even some people that I’m not in touch with anymore. Those are the stories and experiences behind the data that we’re looking at and the reason that I got involved in doing this work.

RENATO BARUCCO: My background is in psychology. I studied in Italy and moved to New York about 15 years ago. At the beginning, for about eight years, I worked in public health and in transgender healthcare services in underserved communities. I was working in South Bronx primarily, but also in Queens and Brooklyn, particularly with transgender women of color. We were providing mainly CDC (but not only CDC) approved interventions for sexual harm reduction, as they used to call it back then, but also making sure that all trans people in the community were connected to healthcare services that were competent and also affordable at the time, since many of them didn’t have insurance. Then, six years ago, I started working at Columbia, and since then, I’ve been focusing not only on transgender health but also on LGBT health as a whole, particularly LGBT aging. KASEY JACKMAN: I came to this work through the clinical route. I went to nursing school at Columbia, where I completed a bachelor’s in nursing and a master’s in psychiatric-mental health nursing. I practiced as a nurse practitioner for a while.

WALTER BOCKTING: I’ve been working with transgender people since 1986 in research as well as clinically, as a psychologist. I came to Columbia after I served on the Institute of Medicine committee that took stock of what was happening across the country in terms of the health of LGBTQ people and the research informing the healthcare. When we did that assessment, we just recognized that a lot of the work had been on HIV and that there was a great need to go beyond HIV to also look at other health concerns that LGBTQ people have. I came to Columbia to help develop and implement a comprehensive research agenda. Given that transgender people were my first love, so to speak, in terms of the work I’ve done all these years, we set out to develop a new study for transgender people, and we wanted it to be longitudinal so that we could actually get a sense of what the lives of transgender people were like over the life course. A lot of the work that had been done up to that point focused more on the time of transition, and we know that people’s lives go on after that, so that was the impetus for Project AFFIRM, the larger project in which we did this recent survey to find out how the people we are following are doing during COVID-19. How did you recruit people for Project AFFIRM? WALTER BOCKTING: We did it through something called venue-based recruitment. We have collaborators in San Francisco and in Atlanta, so in the three cities, we went out to various different venues, both online and offline, where trans and nonbinary people congregate, and we put the word out for our study, and people then signed up. They did that either in

person or via our website, and from that, I think we had about 1500 people that registered for our study. From that, we chose a very diverse group, diverse in gender, diverse in age, diverse in race/ethnicity, for a total of almost 350 people in those three cities. Our goal was not to get as many people as possible; our goal was really to get a very diverse group that was recruited from the community and that we could follow over time.

JEREMY KIDD: One of the strengths of Project AFFIRM, as Walter was saying, is that it’s a cohort that’s been brought together and then maintained now for four years through a lot of engagement and research. The Project AFFIRM team, during more typical times, has also been out in the community and visible at community events. It makes it really easy to reach out to people in some ways because these are folks that all of us have, to a greater or lesser extent, gotten to know over the years.

What kinds of questions were asked in the survey and later in the in-depth interviews? JEREMY KIDD: We focused the survey primarily on the impact of COVID-19 and measures that were taken or recommended by government officials to prevent the spread of COVID-19, so things like physical distancing, social distancing, and the uptake of those things among trans folks in ways that would be expected of anybody in the population, but also in some particular ways. We used a measure called the Pandemic Stress Index, which was developed at the University of Miami, to ask about some of the general ways that people’s lives had changed, in terms of cancelled travel plans, time spent at home, caring for sick loved ones, loss of employment, changes in housing status. We also asked about things that were more particular for this population, such as the loss of access to supports like LGBTQ-specific social supports or trans-specific social supports, community center groups, community organizations that people might have been a part of before but couldn’t access. The other area that we wanted to be sure to ask about were disruptions in gender-affirming care, so whether people had had gender-affirming surgeries that were either cancelled or postponed—I clinically hear from a lot of people who had a lot of difficulty, at various times, attaining gender-affirming hormone treatment, so disruptions in that—as well as disruptions in mental healthcare. We asked about those kinds of things as well. We asked about some other things that we thought might be affected, such as mental health, tobacco/alcohol/substance use outcomes, and sleep to cover other health outcomes that might have been impacted by some of the things that are happening in folks’ lives during the pandemic. WALTER BOCKTING: One of the nice things about doing this in an ongoing group that we’re following is that yes, we’re asking specific questions that are unique to this period of time, but we’re also able to ask them again how they’re doing in terms of their mental health, in terms of substance use, in terms of their wellbeing, so that we can actually see where they changed from previous years.

RENATO BARUCCO: I just started working on this analysis last week, so this is just my impression. We’re still collecting the data and we’re also analyzing in detail what the participants said, but the first impression is that there are a lot of issues, and they are separated into two main categories. One is issues that probably a lot of people are dealing with or dealt with during the months of the pandemic in New York, with isolation and the feeling of being trapped in their apartment and not being able to go outside or to see loved ones or family, and also some changes in their lives: losing jobs, not being able to start a job, or not being able to pursue the plans that they had planned in the months prior to the pandemic. But these are issues that we can expect to find also in the general population.

Within these answers, I see a lot of solitude built upon a very hostile world. You have a hostile environment around you, and you have this community that really helps you negotiate and face some of the struggles, and then all of a sudden you don’t even have that anymore. So that was something that seems to be unique. I see a lot of people saying, “I really miss seeing my friends, and I really miss seeing people I used to go to the park with,” and a lot of people connect with the same people online, but it’s just not the same thing. Another aspect that can come in is disruption in living arrangement, because people couldn’t afford the rent anymore, so one of the roommates left, and now they have an empty room in their apartment and they don’t know who to let into the apartment, because you have to ensure your roommate is understanding, is supportive [of your trans or nonbinary identity]. A lot of people who break up right before or during the pandemic from their significant other also lose an important source of support. The two main things that we’re really noticing so far is the loss of the support system of the community, but also loss of their living arrangement, living situations in general. They also talked about not being able to access healthcare services as much as before. This was very important to some people, especially those who were about to go back on hormones or those who were starting some gender-affirming

procedures, medical procedures, because all of that was interrupted. But I have to say that most of these people said, “I was supposed to have surgery in 3 weeks, but all those sorts of medical procedures are now cancelled, so that’s frustrating, but I also understand that they need to do this, so ultimately I’m going to suck it up and it’s going to be okay for now.”

That was the attitude, their understanding of the situation, while others really felt somewhat more endangered since they weren’t able to access the medical services because they didn’t have internet access or they didn’t know how to have a telehealth visit at the time. I guess that as the pandemic progressed, they probably found other strategies to see the doctors and probably were able to use telehealth. But that’s something that came up quite often as well: access to healthcare services, both in terms of physical healthcare, transgender healthcare specifically, and mental healthcare. WALTER BOCKTING: I think another way of saying what you said, Renato, is that our community, the community that we work with, relies a lot on each other for support, and the pandemic has affected that for many. The ways in which they connect are now suddenly not as easy to access. I think we see that a lot. They have their families of choice, their support in the community, and it has been hard to access that during this time. KASEY JACKMAN: I agree that the loss of social support is really key. In our Latinx substudy, for example, people were not reporting very high levels of discrimination, but just the stress of living as a transgender or nonbinary person in a world that’s not set up for that, as one of our previous participants has expressed it, is very stressful, even if they’re not facing a lot of direct discrimination. I think the loss of that community support is very hard for a lot of people.

As a side note, I recently wore a Project AFFIRM T-shirt to the Queer Liberation March, and on the back, it says “tell your story.” That was our slogan when we started this study: tell your story. It’s a theme that has carried through this longitudinal study and all the substudies. I think it is really important for the community and has benefited our engagement with our participants, that opportunity for them to tell their story. JEREMY KIDD: And as I share with you some of the numbers, I think it’ll become clear why it will be so interesting and helpful to do these in-depth interviews because there are so many things behind some of these numbers. We did a survey near the end of March, shortly after the New York City stay at home order went into effect. Atlanta had not, so you can imagine that it’s a bit of a moving target. We ran the survey until the end of June.

if we think about the evolving nature of that, people who completed the survey in March or April wouldn’t have been able to get a test. People who completed the survey in June would have been able to get a test maybe, but even that has changed again as the pandemic has evolved.

About 70% of the cohort described the impact of the pandemic on their daily lives as extreme or very much in terms of the impact. There wasn’t a single person who said, not surprisingly, that their life wasn’t impacted at all by this. Almost all had been engaged in some sort of social distancing or isolation. This is a number that was very interesting to me: 30% of the cohort was unemployed at this time. However, only 16.7% of those individuals had lost their jobs during the pandemic. This sort of shows what a high unemployment rate there is among trans folks, and there’s lots of research out there describing why that probably is, and a lot of that is related to discrimination. If you look at the 30%, this is probably a comparable number to people that are losing their job in the general population, but about half of the people in Project AFFIRM had already had difficulty accessing employment even before the pandemic. 56.7% reported some sort of personal financial loss during the pandemic, and about 30%, or almost a third of individuals reported difficulty accessing basic needs like food and medications during the pandemic. Over half reported loss of access to LGBTQ-specific supports, and about 40% reported loss of access to transgender/nonbinary specific support systems. 11% had a surgery that was cancelled or postponed. About a third of individuals who are on hormones had experienced some sort of disruption in being able to access hormones. About half of our cohort was engaged in some sort of mental healthcare prior to the pandemic, and about a third of those individuals experienced some sort of disruption in their mental healthcare during the pandemic.

what the ways are that those strategies are falling short, and how we as clinicians and public health researchers might be able to develop tools or interventions that could help provide more support, even in this current environment where we’re not all able to gather together in a room like we used to and hopefully will again soon.

On the Project AFFIRM website, I noticed a particular theme being repeated: promoting resilience, developing resilience, among transgender and nonbinary individuals. I love that goal, because you’re not just finding something with your research, you’re building something and helping people grow. Could you talk about what that means to you?

life experience. So the emphasis on resilience brings forth this other side: we need to understand the problems so we can help people to live fuller, healthier lives, but there’s a lot of existing strength in the community that we can further build on and develop.

WALTER BOCKTING: I’ll say that part of the reason for a longitudinal study is that we have already seen in our data that people learn and adapt over time. Yes, there continue to be challenges, and if anything, there has been a little bit of backlash. A lot of progress was made, certainly visibility, years ago, and the last couple of years have been a bit more challenging as some people have tried to undo some of the progress that was made. So we are seeing how people adapt to that and overall, I expect that the lives of trans and nonbinary people will continue to improve. Perhaps Renato can tell us about a specific example, I’m thinking about our employment study, on what we are doing to promote resilience. RENATO BARUCCO: The employment study is part of Project AFFIRM and we conducted a series of qualitative interviews with some of our participants to understand what some of the challenges were both while seeking employment as transgender or nonbinary people or transitioning while on the job: whether they required any sort of assistance from human resources or if it was something they dealt with by themselves.

For instance, a lot of them reported choosing to work for not-for-profit organizations or LGBT organizations so that they didn’t have to come out or have that conversation all together. But they desired, or they thought about, employment elsewhere.

I also wanted to add, based on what Kasey said earlier, that even in these qualitative answers to the survey, very often you see gratitude toward these ongoing and longitudinal studies. A lot of the open-ended questions start with, “thank you so much for doing this job, a lot of things have changed since last year, but thank you for staying in touch.” I’m paraphrasing, of course. I just really wanted to highlight that because it comes back over and over again. WALTER BOCKTING: I think part of our goal along the way is to have our information inform programs and policies to further promote resilience, improve conditions, and reduce barriers that people face. For employment, we’re going to work with companies and other employers to interest them and engage them into diversifying their workforce for greater inclusion of trans and nonbinary people. JEREMY KIDD: I neglected to mention that one of the other areas that’s included in our survey that we haven’t looked at yet is coping strategies that people utilize. I think that those will be really important to look at for all the reasons that everyone has been saying because that’s where we’re going to learn about the resilience that these individuals already have in their lives. Since these three sites were not impacted in the same way at the same time by the pandemic, it’ll be interesting to see what people are doing to cope with the stress and the isolation in different places, because that might provide insight into what we could think about offering and might be helpful to people in parts of the country that are now being more impacted by the pandemic so that they can learn from the resiliency that other people have been sharing with us. How has research on transgender and nonbinary health changed since you started, and where do you want to see it go in the near and far future? RENATO BARUCCO: As I mentioned earlier, in the first part of my career, I wasn’t necessarily working on research, but we were working with the CDC, and they were doing the research with the data that we were providing them. What I noticed they needed was definitely more opportunities to participate in research and to participate in research that is specific about transgender health. Even ten years ago, all these interventions were about HIV/AIDS. They started realizing that it’s important that we better understand how to provide transgender healthcare, but that wasn’t the goal, necessarily. It became part of the goal, but they were interested in lowering the rate of HIV/AIDS infections and improving HIV care.

KASEY JACKMAN: I agree with Renato. There’s been a mushrooming of transgender health research. I remember when Project AFFIRM started and we went into the field; there were two other large transgender health studies that went into the field the same year. There are increasing opportunities for our community to participate in these research studies, which I think a lot of them appreciate while some of them may feel over-researched or over-examined. One of the things that I think is better recognized now, is that the community really values having trans people involved in the research team. That’s something that comes up often among community members. Participants ask: “are there trans people in this research team?” or they give feedback such as “I appreciated recognizing someone on the research team who I could identify with.” Obviously, the trans population is a small minority, so it may be difficult, but I think that it’s something that researchers increasingly recognize is an important thing to do. And finally, in response to the point about HIV research: even though a lot of trans health research started out as HIV research, some HIV research is still not inclusive of trans people. For example, some HIV research will include transgender women, but not transgender men. So we still see that as an under-studied group within HIV research. WALTER BOCKTING: I will just say that what we talked about earlier, I think, is newer, that we are focusing more on a strength-based perspective. I think it is important to document all the challenges that people face, and we certainly will continue to do that, but it’s also now about resilience and the strengths, and how we can build upon those. I think that’s one of the shifts that I have seen over the years. I’m also thinking about your work, Kasey, that you alluded to earlier: using some emerging methods to look at biomarkers, so not only surveys and people’s self-reporting. As a psychologist, I feel that people’s own perspectives and how they are perceiving things, to me, are always the most important. But we have a fair amount of that which has been done. We’re moving into getting other measures, maybe, Kasey, you could say more about that. KASEY JACKMAN: That was something that was new for our cohort and quite novel for transgender health research in general, to gather different types of data from our research participants. As you were saying, Walter, traditionally, most of the data has been self-reported: we sit down, we interview people or administer a survey online to collect self-reported data, so these newer methods allow us to collect more objective data.

JEREMY KIDD: I think related to that is this idea that research, whether we’re talking about depression, whether we’re talking about substance use, or whether we’re talking about trauma, has moved beyond self-report data. We’ve moved into the era of using MRIs, using biomarkers, using more sophisticated measurements. I think that for trans people, and really, this is a challenging thing for LGBTQ research across the board, our communities really deserve to have research done in the same cutting edge way as these other studies that have primarily cisgender, heterosexual folks, and frankly, mostly men, involved in a lot of clinical trials.

Lastly, what gives you hope for the future? This can be related to your research, science in general, or society at large. Take it wherever you want! RENATO BARUCCO: I think that what gives me hope mirrors what I’m learning from our participants, and that’s technology, which we know really comes with a lot of benefits, but it also comes with some concerns, especially regarding privacy and all of these different companies collecting information. Something that I noticed also from my experience during this pandemic and in the survey answers is that Zoom, Facebook, Instagram, and Reddit, as well as gaming platforms, like Discord, really became a lifeline to keep in touch with others. It’s still not the same, but everyone was mentioning, “I found this online group: it’s not my group or my friends, but at least I have that.” JEREMY KIDD: I was really worried at the start of the pandemic, thinking about queer kids and queer youth, worrying about a lot of college kids who now had to live with their families again and what that was going to be like. But over the course of the pandemic, I bet every other week, I get a Facebook message or a text or an email, sometimes from somebody I don’t know that well, but often people who I’ve known in different phases of my life, who are saying, ‘“my kid just came out to me as queer or as trans or as gay, I want to know how to be supportive of them.” I don’t want to oversubscribe that to COVID, but parents are spending a lot more time with their kids, and kids are spending a lot more time with their parents and learning about them. I think that gives me such hope, to see parents in rural America, where there are not huge queer communities, reaching out and really proactively saying, “how can I be a better parent to my queer kid?” To see that happening in such a consistent, surprising way definitely gives me hope. KASEY JACKMAN: I think the thing that gives me hope is the increasing attention and awareness to gender diversity and incorporating issues of gender diversity into curricula, whether it’s for healthcare providers in training or in schools and universities. Also, at the research level, we’ve had, among our team in the Program for the Study of LGBT health, success in obtaining NIH and private foundation funding for trans studies, which is really wonderful. Those things give me hope. WALTER BOCKTING: I think for me, it’s the increased visibility of nonbinary identities within the community, and I think there’s also risk involved in that, we’ve learned that. For example, our people talk about how being engaged in advocacy is very important to them, but at the same time, that can take a toll on them. I think overall, it’s the increased visibility and the courage of people to stand up and share their experiences, share their story with us, including stories that are more diverse than the traditional narrative of transgender people. I think that really gives me hope, and I think it’s wonderful for the next generations, so that there will be a range of gender identities and expressions that they can relate to and find a sense of belonging with. Interview Highlights: Providing Cardiac Care for Pregnant Women During COVID-19 With Jennifer Haythe7/15/2020

By: Hannah Lin (CC '23)

The following is a heavily condensed version of the full interview. If you're interested, read more here. Could you talk about the COVID-19 research that you’re involved in?

Finally, I do cardiac obstetrics, which is the care of pregnant women with heart disease, and the obstetrics group published a paper with guidelines on how to do telemedicine visits with pregnant women with different medical problems. I participated in the section on cardiac problems during pregnancy, how to manage during COVID, and what the recommendations would be for how to integrate televisits with in-person visits. How are you seeing pregnant women being uniquely affected by this pandemic?

You dedicated yourself to patients on the frontlines along with other healthcare providers during the peak of the pandemic in New York City. Could you talk about how you felt then and how you feel now, a few months after? I think at the beginning, it was really very stressful. I have two children who are 12 and 15. We’re lucky enough that we have a family country house upstate, so my husband took them there, but then that meant that we were apart for chunks of time, which was hard.

another, took care of each other, making sure that they were okay, they were safe. I felt the hospital handled it incredibly well from an organizational perspective, being very transparent, providing a lot of information.

I think for me personally, it was pretty hard in the beginning, having to travel to see my family, the unknown, the anxiety. I did feel like I had a lot of insomnia. It’s funny you asked because just, I would say, the last week or two, I’ve been starting to feel much more back to myself. I’m not wearing scrubs anymore, I’m wearing normal clothes, and I don’t have to wear Crocs! That’s been a lot better. But it was a good three months that were very challenging. We saw some of our colleagues become very sick and thought some of them would die, we know some people who died, and I think that was emotional for everybody. Lastly, what gives you hope for the future of cardiology, medicine, and society as shaped by everything that has happened this year (the pandemic, the fight for anti-racism)?

hopeless, I’ve seen so much goodness in people during this outbreak in the hospital, whether it’s nurses, doctors, travel nurses from the South who came up to work with the sickest of the sick COVID patients with a smile on their face and FaceTimed the families.

I just always remind myself that there are so many people that are inherently good and that we’re bombarded with all this social media showing how terrible people can be. If you try to push through all that and focus on what you see around you, you’ll see that so many people deep down are incredibly kind, brave, and inspiring. The third, in terms of social justice, I think that in medicine, this has become an incredibly important thing to focus on, not only in providing equitable healthcare to all different kinds of minorities, which is a big focus for me in terms of cardiac obstetrics, knowing that the maternal mortality rate in this country is incredibly high, particularly among Black women, but across all areas of medicine. I think, at Columbia, they are making every effort, as they should, to make all minorities feel like they have no barriers, that they are not being discriminated against, that we are all equal and the same, and are taking note of past decisions that were not acceptable and trying to make changes as a result of that. Full Interview: Providing Cardiac Care for Pregnant Women During COVID-19 With Jennifer Haythe7/15/2020

By: Hannah Lin (CC '23)

Can you talk about your background in medicine and research and how you got into cardiology? My path to cardiology was interesting. I really enjoyed cardiology as a resident, and at the time, there were only four cardiology fellows per year. You had to apply during your second year of residency as opposed to your third year, so you had to apply a year in advance of finishing residency. I wanted to start a family and felt like cardiology seemed very male-oriented and required frequent overnight calls. It didn’t seem like a lifestyle that was very appealing to me, so I actually initially matched in pulmonary critical care. I was in my gap year working in a clinic, and I ran into Donna Mancini, who was head of the heart failure transplant group at the time, in a garage elevator. She had been one of my attendings on the ward service when I was an intern and she asked me what I was doing. I explained to her what I had wanted to do and what I was doing, and she asked, “Well, why don’t you just drop pulmonary and come do a heart failure fellowship with me and work for me?” I thought about it and said I would do it. I did that for a year, and then I worked as a hospitalist for her for two years, and then she came to me and said, “I really think you should do a cardiology fellowship.” They were expanding the fellowship, so I was able to start as a general fellow the next year and then I went back to work in heart failure transplant after that. That definitely is a very interesting path. Fast forwarding to now, could you talk about the COVID-19 research that you’re involved in? I was involved with a group of cardiologists at the hospital led by Dr. Sahil Parikh which published an article in JACC about the cardiac manifestations of COVID early on, trying to draw attention to the fact that it wasn’t only ARDS that we were seeing but also plenty of cardiac manifestations like myocarditis, heart failure syndrome, stress cardiomyopathy, and arrhythmias. We are also awaiting acceptance on a paper about women and COVID, looking at why women seem to get COVID less, what some of the reasons are for that, what some of the socioeconomic impacts are for women getting COVID and the types of jobs they do, whether they really get COVID less or are just not getting diagnosed as much because they are less likely to come to the hospital. We were trying to tease some of that out. Finally, I do cardiac obstetrics, which is the care of pregnant women with heart disease, and the obstetrics group published a paper with guidelines on how to do telemedicine visits with pregnant women with different medical problems. I participated in the section on cardiac problems during pregnancy, how to manage during COVID, and what the recommendations would be for how to integrate televisits with in-person visits. I was just about to ask you about your work in obstetrics. How are you seeing pregnant women being uniquely affected by this pandemic? I think that the division has done a really good job of trying to stay very connected with their pregnant patients and trying to do outpatient visits on pregnant women. There was a very interesting paper published in the NEJM about the COVID positivity rate in all women admitted for delivery, and they reported a pretty high incidence of asymptomatic COVID positivity in the community of women who were coming in, some of whom became symptomatic during their pregnancy, some of whom may have thought they were asymptomatic but were having symptoms of labor which may really have been symptoms of COVID. The positivity rate was 13.7%, which was high, and not expected, at the time, and provided insight to us about how much undiagnosed COVID was in the community. I think women have had a hard time in the labor and delivery world, especially initially, because the hospitals put restrictions on visitors, and I think there was about one week there when women who were pregnant were not allowed to have any visitors with them during delivery, which was incredibly difficult and emotionally taxing on these women. That actually ended up getting reversed, and they were allowed to have one visitor with them during the delivery. I think it’s been very stressful for pregnant women, since they’re having this beautiful thing happen to them, and they’re wearing a mask, their partner’s wearing a mask, everyone in the room is wearing masks and gowns, and it’s not exactly the warm and fuzzy delivery that people may have imagined for themselves. In terms of illness, we haven’t had any deaths in pregnant women from COVID. We’ve had women get sick after delivery and need medical care for COVID, and I actually couldn’t tell you right now what the transmission to the fetus is in our institution, I believe it’s either zero or very low. Going back to the televisits, you wrote an op-ed in The Wall Street Journal titled, “House Calls are Back—Virtually.” Unfortunately, I don’t have a subscription, but I could read the first paragraph, where you talked about how virtual visits give you surprising insights into your patients’ health. What do you think the future of telemedicine looks like specifically for your specialty, cardiology? I think telemedicine is an incredibly useful tool, and I know that there’s been a lot of pushback, especially from community physicians who see a large volume of outpatients. I think that billing is obviously an issue for people trying to run a business in medicine. But there were a lot of rapid changes made that allowed for telemedicine to take off that I don’t think could have happened without COVID in terms of regulatory requirements and crossing state lines, having the ability to see people in different states where you’re not licensed but still allowed to do televisits with them. I think telemedicine is amazing. I know that there is always going to be resistance to new things, but I think it really fills a void especially for people of lower socioeconomic status, assuming that they have access to some kind of a smart device, people who are very disabled and for whom it’s very hard to get to the hospital, people who aren’t feeling great that day and can still be seen, people during COVID who were nervous to come to the hospital or who needed to minimize their exposure. I also hope, in the future, that people will be able to consult with specialists that aren’t near their home and get ideas and recommendations that don’t require a huge cost to the patient to travel and see that specialist. I like to give the example that someone has a rare brain tumor, lives in a rural part of the country, and doesn’t have the resources to just take a trip to Chicago, New York, or some major medical center. They can have a visit with a neurosurgeon that specializes in that kind of tumor and a specialty board, and those specialists can review the images with the family and make a recommendation that can help them decide what they want to do. I think that telemedicine is going to make it much easier for people to get those kinds of consultations. I think that it’s going to be here to stay. I think that people are going to fill in the gaps in between regular visits in order to keep better tabs on people’s health, especially heart failure. For me, it’s great, because we can have a video visit where you can tell me what your weight is, you can show me if your legs look more swollen, I can see if you look short of breath, I can adjust medications, or I can say you need to come into the hospital. Obviously, procedure-based professions are going to be a little more challenging. You have to be here to get a procedure, but you could have all the workup done when the proceduralist does a televisit with you and then you can schedule the procedure right after. So it’s not totally useless for proceduralists, but there are specialties where it would be a bit more difficult. Dermatology might be hard; sometimes, you really can’t see as well on these video visits as in other types of things. Obstetrics, you need to examine the patient and see how far along the baby is, what’s going on, and they need to get ultrasounds. So there are areas where it’s more challenging, but for my group, it’s great. Shifting away a bit, it’s been about three months since the peak of the pandemic in NYC. You dedicated yourself to patients on the frontlines along with other healthcare providers, away from your family, and a lot of providers have spoken out about the huge physical and mental burden they felt and still feel. If you’re comfortable talking about it, I thought I could give you some space to talk about how you felt then and how you feel now, a few months after. I think at the beginning, it was really very stressful. I have two children who are 12 and 15. We’re lucky enough that we have a family country house upstate, so my husband took them there, but then that meant that we were apart for chunks of time, which was hard. I think, especially for my younger child, there was a lot of anxiety around my health and wellbeing, whether it was safe to come home and see them, and whether I could reenter the home safely. The beginning was really hard. I think it took a big emotional toll on many of us and I think there was a huge amount of fear because we hadn’t dealt with it before. What we were seeing was really at the level of chaos and war. It felt like a situation that no one had ever seen. Practically the whole hospital was COVID, every ICU bed was COVID except for one unit, popup ICUs were all over the hospitals, some had to have two patients to a room, some operating rooms had four patients to a room. I was actually incredibly overwhelmed in a positive way by my colleagues and how hard everybody worked, how devoted everyone was, how much they looked out for one another, took care of each other, making sure that they were okay, they were safe. Pretty much every surgeon in the whole hospital wasn’t doing surgery, and they formed a group to go out and put in lines in all the patients so that people didn’t have to fumble around with putting in lines in someone with overwhelming COVID. That was amazing. I felt the hospital handled it incredibly well from an organizational perspective, being very transparent, providing a lot of information. Dr. Craig Smith wrote these daily missives about the experience which were very uplifting. I think for me personally, it was pretty hard in the beginning, having to travel to see my family, the unknown, the anxiety. I did feel like I had a lot of insomnia. It’s funny you asked because just, I would say, the last week or two, I’ve been starting to feel much more back to myself. I feel safe in the hospital. Obviously, the numbers of patients have dramatically reduced, we have a lot of data to show that PPE works really well and there was very low transmission to healthcare providers once we started using PPE, and I’ve been starting to see patients in the clinic again, so even today felt like a normal day. I’m not wearing scrubs anymore, I’m wearing normal clothes, and I don’t have to wear Crocs! That’s been a lot better. I can sleep again. But it was a good three months that were very challenging. We saw some of our colleagues become very sick and thought some of them would die, we know some people who died, and I think that was emotional for everybody. Thank you so much for sharing that. For students interested in going into medicine and specifically cardiology, do you have any advice or life lessons that you would like to impart? I would say that medicine is a great profession, no matter what everybody else says. One thing I didn’t mention earlier was the toll that it took, seeing all these patients in the hospital who didn’t have their family members with them when they were dying or were very sick. The emotional support having to come from nurses and doctors there to try to help them communicate with family was very distressing but also showed how important our job is and really reminds everybody that medicine is a calling and that when things get crazy, your job is still really important. You don’t sit home and conduct business as usual over the internet, you really are in the trenches taking care of sick people. I think that cardiology is a great field. I wish more women would go into cardiology. You don’t have to do any procedures to be in cardiology, like me. If you want to do procedures, there’s plenty of them. The thing about medicine now is that there are so many different ways to practice it. You can be a cardiologist who only does echo, you can be an interventionist, you can be a general cardiologist, you can be an EP specialist. The same goes for all specialties. You can get as specialized or as general as you want, you can carve out the lifestyle you want in terms of how much you work. I’ve always thought medicine is a great career for women. The one area that is not as great is that we need to see more women being promoted and in positions of power. That goes for the entire country. I think people should know that it’s normal to doubt whether medicine was the right choice when you’re in medical school and residency. I think a lot of people ask what they’re doing there, why they did this, they feel tired, they feel useless, they feel stupid, they feel like they made the wrong choice and wasted all this time and money. But I think that if you can just keep going and find some people to talk to, you’ll realize that when you get to the other side, you’ll feel really lucky to have this job. I feel really lucky to have made this choice. Lastly, to end with some optimism: what gives you hope for the future of cardiology, medicine, and society as shaped by everything that has happened this year (the pandemic, the fight for anti-racism)? From a medicine perspective, I feel very hopeful because I think we’re really on the cutting edge of a whole new way of practicing medicine in terms of drug design and targeted therapies. For diseases that were very hard to treat, I think in the next 10-20 years we’re going to see a huge change in how cancer’s treated, how heart disease is treated, how for so many illnesses, even neurologic diseases, genetic therapies and targeted therapies are going to make a huge difference for the treatment of people and hopefully become less and less invasive, which we can see in cardiology with the advent of TAVR. There are very few reasons to have a surgical aortic valve replacement at this time, and eventually, that’s going to be true for so many other surgeries. That’s one. From a societal perspective, I feel like despite how stressful and chaotic everything in the world is right now and sometimes people feel hopeless, I’ve seen so much goodness in people during this outbreak in the hospital, whether it’s nurses, doctors, travel nurses from the South who came up to work with the sickest of the sick COVID patients with a smile on their face and FaceTimed the families. I just always remind myself that there are so many people that are inherently good and that we’re bombarded with all this social media showing how terrible people can be. If you try to push through all that and focus on what you see around you, you’ll see that so many people deep down are incredibly kind, brave, and inspiring. That’s the second. The third, in terms of social justice, I think that in medicine, this has become an incredibly important thing to focus on, not only in providing equitable healthcare to all different kinds of minorities, which is a big focus for me in terms of cardiac obstetrics, knowing that the maternal mortality rate in this country is incredibly high, particularly among Black women, but across all areas of medicine. I think, at Columbia, they are making every effort, as they should, to make all minorities feel like they have no barriers, that they are not being discriminated against, that we are all equal and the same, and are taking note of past decisions that were not acceptable and trying to make changes as a result of that.

By: Hannah Lin (CC '23)