|

By Kimberly Shen

Editor Bryce Harlan “Out, damned spot! Out, I say!” These were the words Lady Macbeth uttered as she tried to wash away imagined bloodstains. Famous for the pangs of conscience she experiences after acting as an accomplice in King Duncan’s murder, Lady Macbeth draws attention to the perceived connection between physical cleansing and moral purification by attempting to cleanse her hands to free herself from guilt. Indeed, this link is found in many cultures around the world, for the act of cleansing is a coping mechanism that is believed to bring about the purity of the soul. This concept is manifest in a number of religions, including Christianity, Islam, and Hinduism. Certainly, research on the link between physical and moral purity suggests that people are predisposed to connect categories based on bodily experience (clean versus dirty) with social categories (moral versus immoral). Two researchers named Chen-bo Zhong and Katie Liljenquist worked to explore this connection in order to better understand the Lady Macbeth effect–a priming effect characterized by an increased response to cleaning triggered by feelings of shame. In each set of tests, researchers asked participants to recall an ethical or unethical act they committed in the past. The researchers then asked some of the participants to fill in the missing letters in a number of incomplete words, such as W__ __ H and SH__ __ ER, and some of the participants to choose between a pencil and an anti-septic wipe. Participants who recalled ethical acts returned words like WISH and SHAKER, and largely chose the pencil (three-quarters of the time). In contrast, the subjects who were asked to think of unethical acts mostly returned WASH and SHOWER, and chose the anti-septic wipe three-quarters of the time. To further test whether the act of physical cleansing had any effect on feelings of guilt, Zhong and Liljenquist asked every participant to recall an unethical act and type a description of it into a computer. They then told half of the participants that the keyboard was dirty and gave the participants a chance to wash their hands. Afterwards, the researchers asked each of the subjects if they would be willing to work as unpaid volunteers for a study. Interestingly, the participants who washed their hands were far less likely to volunteer than the subjects who did not wash their hands. This result suggests that feelings of guilt can, to some extent, be “washed away.” After all, the relationship between bodily and moral purity is not only rooted in cognition, but also in emotion. A gustatory emotion that has developed through evolution as a safeguard against unsafe food, disgust, is now culturally associated with aversion towards social and moral wrongdoing. Certainly, the experience of “amoral” or “gustatory” disgust and the experience of “moral” disgust have some biological overlaps–pure disgust and moral disgust bring about similar facial expressions and stimulate overlapping areas of the brain, including the frontal and temporal lobes. Given this, physical cleansing is implied to reduce self-feelings of moral condemnation due to the overlapping physiological and neurological relationships between physical and moral disgust.

0 Comments

By Allie DeCandia

Edited by Arianna Winchester Humans have a love affair with plastic. Lightweight, versatile, durable, and inexpensive synthetic polymers have flooded the global market since 1950. Yet the qualities that earn success in the marketplace also severely endanger the natural environment. Winds, rivers, and currents ferry lightweight refuse ocean-bound, and cooler temperatures and UV-protection render it long lasting. Plastic floats in bodies of water for decades before degrading into “microplastics,” but even these miniscule particles pose risks to ocean life. They mingle with professional fishing gear and “ghost nets” that wander around the ocean silently seizing marine mammals. Because of these microplastics, the limbs of aquatic life get entangled, digestive tracts occluded, and tissues infused with toxins. Entanglement occurs when marine mammals are constricted or entrapped by anthropogenic debris. This may lead to strangulation, open sores, impaired behaviors, increased energy expenditure, and, in extreme cases, drowning. Take for example, New Zealand fur seals, which can get caught in stray lobster traps, but aren’t strong enough to carry them to the surface, so they remain trapped. Similarly, Dugongs are unable to wriggle free from the constraints of fishing nets. Even humpback whales, if not freed from tows of nets, ropes, and plastics tangled around their flukes, sometimes die from exhaustion in their struggle to break free. Unfortunately, ocean debris acts as an anchor for these trapped animals. Even stray monofilament lines can lock animals down to the ocean floor, dooming them to a slow, painful death. The second threat stemming from the misuse of plastics, ingestion, occurs when organisms mistake debris for food. Plastics come in all shapes, sizes, and colors, so plastic debris can often mimic the look of mammalian food. Analysis of polar bear scat, for instance, revealed ingestion of debris like foil, cardboard, cigarette butts, duct tape, foam rubber, glass, paint chips, paper, plastic, wood, and even a watch band. While these items luckily passed through the animal, others often do not. Since synthetic materials do not degrade as organic ones do, ingestion can often yield wounds both internally and externally, gastro-intestinal blockages, false sensations of satiation, toxin bioaccumulation in tissues, impaired feeding capability, and even starvation. In 2008, examination of the stomach contents of two sperm whales stranded in northern California uncovered ropes, plastics, and 134 different types of fishing nets. One whale died of a ruptured stomach; the other of starvation. Both deaths were directly caused by debris ingestion. Marine mammals are fairly diverse, so often times the distinct behaviors, morphologies, and habitat requirements render certain risks more threatening to one type of organism over another. The order Carnivora, which contains polar bears, sea otters, and pinnipeds, dwell at the intersection of land and sea. These animals seem to approach their dual environments with a sense of curiosity. As a result, marine debris poses a particular risk of entanglement as they excitedly explore their surroundings. Pinnipeds are drawn to novel items such as plastic bags or abandoned nets, and often accidentally slip their heads inside loops and holes. Then, since the animal is unable to escape, these “lethal necklaces” remain on the neck of the pinniped, constricting the animal as it grows. For some species, such as the critically endangered Hawaiian monk seal, entanglement has been implicated as a major threat to population growth. Even a seemingly modest rate of entanglement of 0.04%-0.78% has proven detrimental to an ailing population. The order Cetacea consists of mysticetes (baleen whales) and odontocetes (toothed whales). Unlike pinnipeds, cetaceans are entirely marine, large bodied, and migratory. Ingestion is therefore the greatest threat to these animals. Nets and plastics can become tangles at the bottom of the ocean and prevent them from feeding. On a smaller scale, microplastics join the krill that these animals inhale with every gulp or skim of the surface. When the animals filter feed, those synthetic particulates enter their bodies and in the case of Mediterranean fin whales that were examined, the plastics leech toxins into their tissues. Odontocetes largely avoid these risks associated with filter feeding. However, their large-scale ingestion of marine debris does cause plastic impaction, gastro-intestinal tract blockages, starvation, and gastric rupture. The final order, Sirenia, contains dugongs and manatees. Like cetaceans, sirenians spend their entire lives submerged beneath the waves of aquatic environments. Unlike cetaceans, they travel through coastal waters, estuaries, and inland river networks. While herbivory precludes the risk of bioaccumulation, entanglement and ingestion still pose a threat to these species. When we think about the popularity of plastics in our society, it seems that the threat of entanglement and ingestion is inevitable. However, through the implementation of stringent legislation, recycling initiatives, incentive programs, consumption reductions, and citizen-led clean up efforts, this does not have to be the case. All it takes is education, activism, and compliance on our part. While the ocean can never be completely devoid of plastic, we can prevent further degradation from this point on. Through increased awareness, it is possible that marine mammals won’t have to live in an environment inundated by trash. By Ian Cohn

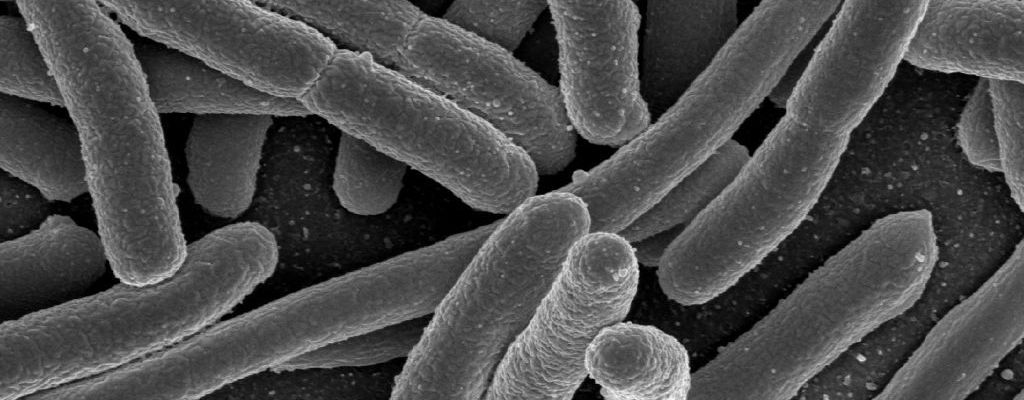

Edited by Josephine McGowan Scientists have long warned of the impending “age of antibiotic resistance.” As doctors use antibiotics more frequently and liberally, the potential for bacteria to develop drug-resistant mutations and transform into “super-bugs” becomes ever higher. At its worst, this means that eventually, we will stand powerless to these drug-resistant super-bugs, no longer able to count on our library of antibiotic weapons which we have relied on so assuredly since Alexander Fleming’s discovery of penicillin in 1929. Though such a prescription seems grim and outlandish, until recently, new antibiotics had not been discovered since 1987, feeding the peripheral fear of a potential new Dark Age that has plagued the imaginations of doctors and medical researchers. However, in January of this year, researchers at Northeastern University provided a much-needed sigh of relief as they announced the discovery of a novel antibiotic, Teixobactin. Teixobactin, like many other antibiotics, inhibits bacterial cell wall synthesis, but its mechanism of doing so is particularly intriguing. Unlike other antibiotics, Teixobactin works by binding to important components of the cell wall that are common to most bacteria. Because the lipids that are bound by Teixobactin are common across bacterial species, the possibility of a drug-resistant mutation is potentially lower in response to Teixobactin, as it is unlikely that a bacterium can develop a functional substitute to these two important cell wall components. While the discovery of the new compound itself is important and brings with it the potential for treatment of drug-resistant bacteria, the most exciting part of the recent discovery is not the Teixobactin itself but is in the methodology used to obtain it. Scientists wishing to discover new antibiotics have long been hindered by the need to culture the bacteria that produce the antibiotics in a lab setting. Often, the bacteria are unable to grow in these unnatural environments. The method used by the researchers at Northeastern, however, mitigates this problem by allowing the bacteria to grow in soil—an environment these bacteria are accustomed to—but still allows for the extraction of potential antibiotic compounds. To accomplish this technique, scientists used a device called the iChip that allows for single bacterial cells to grow in diluted soil. The iChip is placed in a soil sample, providing the bacteria with a more appropriate environment in which to grow than a petri dish, and allowing scientists to keep individual colonies isolated. Once the bacteria begin to grow in in the iChip environment, colonies are isolated and extracted to grow in vitro, where they are able to grow more efficiently since they had somewhat of a “kick-start” in the soil. This novel method can be adapted in the future to grow different bacterial strains that may serve as potential sources for other antibiotics. Despite these promises, letting our “super-bug” guard down completely would be shortsighted and irresponsible. Teixobactin has yet to be tested in humans, and it is possible that it may be too difficult to administer or dysfunctional in human immune systems. In addition, the mechanisms by which bacteria obtain drug-resistance are not fully understood, so there may still be an unknown method through which bacteria become mutated to resist Teixobactin. Nonetheless, the iChip method gives hope in the antibiotic world and provides us with a new pathway to potentially circumvent, or at least stave off, the prophetic age of antibiotic resistance. By Ruicong (Jack) Zhong

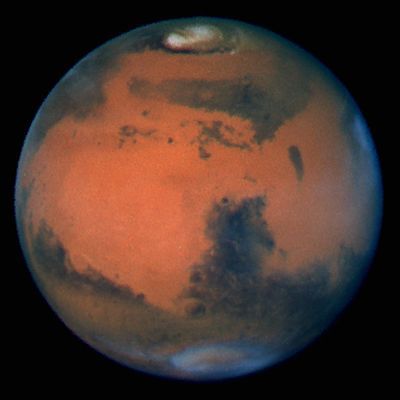

Editor Arianna Winchester With the release of many thought-provoking science fiction movies on space exploration, such as Interstellar, many people have begun to wonder if we too will inhabit planets in distant solar systems. While we look out farther into the universe in search of compatible Earth-like planets, we are overlooking a prime candidate for human colonization in the future: Mars. As time progresses, our need to start a human settlement on another planet is becoming increasingly clear. The danger of catastrophic events happening on Earth is imminent, even if there is only a small chance of such events happening. For instance, the onset of a nuclear war is a threat to all life. Starting a colony on another planet would give us some security in case of an apocalyptic event. Even if a habitable planet in a distant solar system can be found within the next 10 years, the possibility of ever reaching such a planet is slim with our current technology. The nearest star system, Alpha Centauri, is 4.3 light years away. That means if astronauts will be able to travel at the speed of light (3×108 m/s)—an impossible task with present-day spacecrafts—about 4 years will pass on Earth before they reach the destination. Currently, only one human spacecraft, Voyager 1, has ever left our solar system, yet Voyager is traveling at a snail’s pace of 1.7×104 m/s. Granted, the development of such vehicles may be possible if there is a breakthrough in physics research or engine technology. However, we can’t depend on such breakthroughs to happen anytime soon. Even if we get there, there is no guarantee that a faraway planet is habitable for life, since we have not sent any probes to scout out the real estate. Even on this planet, we’ve seen how traversing new territory without previous knowledge can be dangerous. While exploring the Americas, many European colonists died after successfully crossing the Atlantic since they didn’t know anything about the climate or conditions. Without knowledge of the destination, the space colonists might fall victim to similar misfortune. Instead, we should start by looking much closer to home. We know Mars will take about 1 year to reach using current spacecrafts. That is comparable to the voyage between Europe and the Americas in colonial times. Since we have sent rovers and probes to Mars, we have a good grasp of the conditions on the planet. Such knowledge is crucial for the effective planning of a mission. We also know that Martian climate can potentially be hospitable to humans: temperatures on Mars can reach a comfortable 70°F near the equator. Mars also does appear to have water and methane underground. An average Mars day is 24.6 hours, similar to that on Earth. Lastly, we know that even though Mars’ gravity is 38% of Earth’s gravity, it is still much stronger than gravity on the moon. All of these factors make Mars a great candidate to support human life in the future. Still, Mars does require much work to become as welcoming of a home as Earth. Mars lacks a strong magnetic field and thick atmosphere like Earth’s to protect the surface from cosmic radiation. Too much cosmic radiation can cause mutations in our DNA that can trigger cancerous growth. Also, temperatures on Mars can get extremely cold in certain areas of the planet. To make the colonization of Mars possible, we are currently in the process of developing technology to tackle those issues and more. One of the most costly aspects is the rocket we would need to get there. SpaceX, a space transport company, is developing reusable rockets, which would dramatically reduce the price of rocket launches. To deal with cosmic radiation, colonists could hypothetically bury their Martian habitats under a thick layer of soil and surround them with radiation shielding materials like lead. Mars residents could use solar power to provide heating and lighting in the place of fossil fuels abundant only on Earth. Looking even further into the future, we may eventually colonize more distant planets, but Mars is our best option at the moment—and a pretty good option, too! Author Ian MacArthur

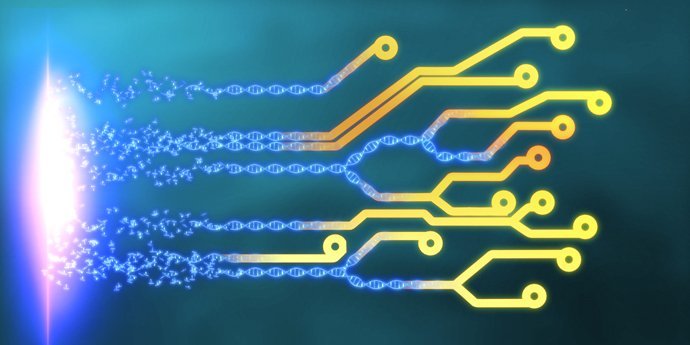

Editor Josephine McGowan Electronic circuits are the backbone of modern civilization. The logical processes they perform underlie the function of all computational devices, ranging in complexity from the simplest calculators up to the most advanced supercomputers. However, the execution of logical tasks need not be confined to inorganic circuitry. Extensive research has been devoted to the development of synthetic biological circuits, amalgamations of cells that are able to interact with their surrounding environment and respond in precise ways. The logical functions of basic electronic circuits occur through responding to inputs with specific outputs. A group of cells mimics this process on a genetic level. Molecules in the environment around a cell may bind to plasma membrane receptors and signal the cell to manufacture a specific gene product. Such pathways are an integral part of how cells naturally regulate their metabolism in response to the external environment. For example, lactose induces the production of the enzyme b-galactosidase (b-gal) in E. coli, which then cleaves the sugar into glucose and galactose. In the absence of lactose, the cell does not manufacture b-galactosidase because a repressor protein is bound to the operator of the b-gal gene. An operator is a regulatory region of DNA whose state determines whether a gene will be expressed. Lactose binding to the repressor protein causes it to dissociate from the operator, allowing gene expression to be carried out by enzymes binding the promoter, another regulatory DNA region that initiates gene transcription. Evolution has tailored genetic circuits to be highly precise. All of the genetic machinery of a cell is suited for the natural inputs it may receive. The challenge in constructing synthetic biological circuits, then, is to use this existing machinery to enable the cell to respond in new and precise ways. Diabetes, for instance, has been imagined as a potential therapeutic application of biological circuits. An artificial probe composed of glucose-sensitive cells might circulate in the blood of a diabetic and monitor glucose levels. At a specific threshold, the sensor cell would begin to produce and release insulin, or signal a cell downstream in the circuit to do so. Glucose, however, is a common biological signal that may induce a cascade of events when present in a cell. If the effect of glucose on the circuit is not precisely controlled, it may affect metabolism or gene expression in undesirable ways. To address this problem, researchers may have to extensively remodel the genome of circuit cells by inserting repressible and inducible gene promoters to ensure the cells respond to stimuli as intended. Another challenge in designing synthetic biological circuits is accounting for the complexity of biological conditions and environments. A circuit intended to detect toxic conditions in the body may have to respond to several molecules in combination that, when present independently, are not indicative of pathological conditions. In 2012, MIT scientists announced the development of a synthetic biological circuit capable of detecting four molecular inputs. Further expansion and refinement of input sensitivity will be necessary if circuits are to be widely applied for therapeutic purposes. Cancer is likely the most problematic disease for synthetic circuits to address. The close resemblance of cancer cells to healthy cells means that a circuit designed to detect cancer would have to be capable of sensing subtle molecular differences between these cell types. Moreover, if the circuit was engineered to release a cytotoxic agent or initiate an immune response against cancer, the delivery of the output drug or signal must be designed to avoid healthy tissues. Presently, synthetic biological circuits are several years away from commercial and medical applications. However, the specificity in detection and response they can provide poses them as an intriguing solution to some of our most difficult biological and medical problems. Just as in the case of electronic circuits, the ceiling for biological circuit sophistication and utility promises to be high. |

Categories

All

Archives

April 2024

|