|

By Ian Cohn

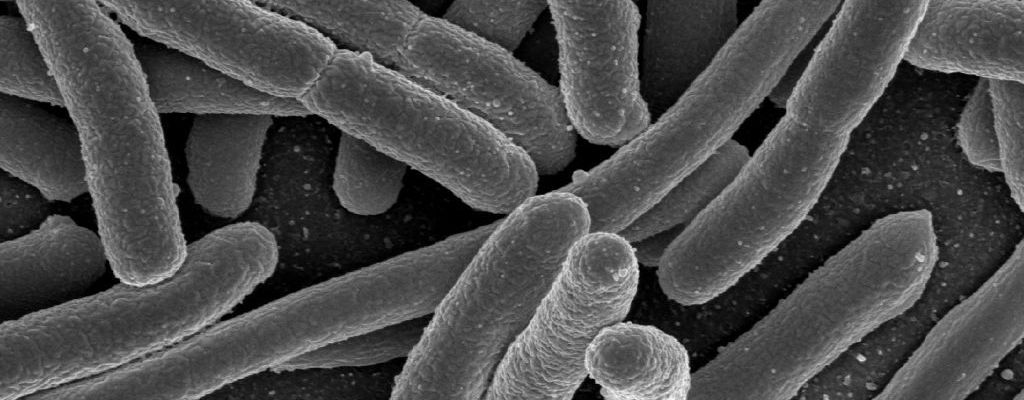

Edited by Josephine McGowan Scientists have long warned of the impending “age of antibiotic resistance.” As doctors use antibiotics more frequently and liberally, the potential for bacteria to develop drug-resistant mutations and transform into “super-bugs” becomes ever higher. At its worst, this means that eventually, we will stand powerless to these drug-resistant super-bugs, no longer able to count on our library of antibiotic weapons which we have relied on so assuredly since Alexander Fleming’s discovery of penicillin in 1929. Though such a prescription seems grim and outlandish, until recently, new antibiotics had not been discovered since 1987, feeding the peripheral fear of a potential new Dark Age that has plagued the imaginations of doctors and medical researchers. However, in January of this year, researchers at Northeastern University provided a much-needed sigh of relief as they announced the discovery of a novel antibiotic, Teixobactin. Teixobactin, like many other antibiotics, inhibits bacterial cell wall synthesis, but its mechanism of doing so is particularly intriguing. Unlike other antibiotics, Teixobactin works by binding to important components of the cell wall that are common to most bacteria. Because the lipids that are bound by Teixobactin are common across bacterial species, the possibility of a drug-resistant mutation is potentially lower in response to Teixobactin, as it is unlikely that a bacterium can develop a functional substitute to these two important cell wall components. While the discovery of the new compound itself is important and brings with it the potential for treatment of drug-resistant bacteria, the most exciting part of the recent discovery is not the Teixobactin itself but is in the methodology used to obtain it. Scientists wishing to discover new antibiotics have long been hindered by the need to culture the bacteria that produce the antibiotics in a lab setting. Often, the bacteria are unable to grow in these unnatural environments. The method used by the researchers at Northeastern, however, mitigates this problem by allowing the bacteria to grow in soil—an environment these bacteria are accustomed to—but still allows for the extraction of potential antibiotic compounds. To accomplish this technique, scientists used a device called the iChip that allows for single bacterial cells to grow in diluted soil. The iChip is placed in a soil sample, providing the bacteria with a more appropriate environment in which to grow than a petri dish, and allowing scientists to keep individual colonies isolated. Once the bacteria begin to grow in in the iChip environment, colonies are isolated and extracted to grow in vitro, where they are able to grow more efficiently since they had somewhat of a “kick-start” in the soil. This novel method can be adapted in the future to grow different bacterial strains that may serve as potential sources for other antibiotics. Despite these promises, letting our “super-bug” guard down completely would be shortsighted and irresponsible. Teixobactin has yet to be tested in humans, and it is possible that it may be too difficult to administer or dysfunctional in human immune systems. In addition, the mechanisms by which bacteria obtain drug-resistance are not fully understood, so there may still be an unknown method through which bacteria become mutated to resist Teixobactin. Nonetheless, the iChip method gives hope in the antibiotic world and provides us with a new pathway to potentially circumvent, or at least stave off, the prophetic age of antibiotic resistance.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Categories

All

Archives

April 2024

|