|

By Jenna Everard

We all have digital data—texts, emails, essays, photos... the list goes on and on! And we all need to store it. To do so, we have flash drives, hard drives, servers, entire rooms lined with servers, and entire buildings filled with servers. The International Data Corporation has predicted that by 2025, the “global datasphere,” an entity that encompasses all the data created, captured, and replicated, will be around 175 Zettabytes, or 175 trillion gigabytes, in size. For perspective, if all that data was stored on DVDs, the stack of these DVDs would stretch around the Earth 222 times! With such rapid growth in data, it is likely that our infrastructure and capacity to store it will be tested. But what if the solution for doing so was just at our fingertips? Yes, literally at our fingertips, because the solution might just be our DNA.

0 Comments

Kevin Wang

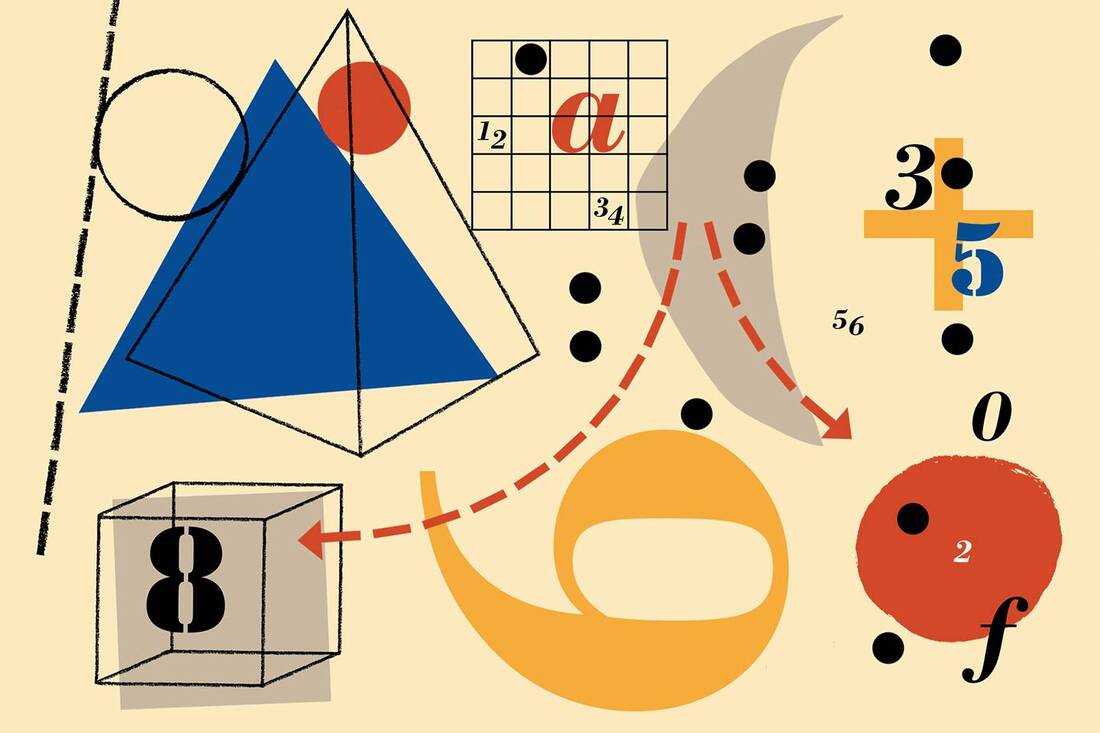

In 2000, the Clay Mathematics Institute published the Millenium Prize Problems. These were seven mathematical problems, and solving any one of them came with the award of one million dollars. However, they were also some of the most complex, unsolvable problems of the past few centuries. Many appear intimidating just from their name—the Riemann Hypothesis, the Yang-Mills Existence, and Mass Gap, just to name a few. The very first problem on the list, though, looks easy enough, almost like a middle school algebra equation. It is simply titled “P = NP.” By Tanisha Jhaveri

Think about a childhood story you have. There may be some details that you recall more vividly, while others are a little fuzzy. Now imagine trying to recount this story to someone. You will probably have to fill in some details that you don’t fully remember. For example, if the events took place in the morning, you might assume that you ate breakfast, despite not specifically remembering so. This subconscious process of introducing new pieces of information can alter your own recollection of the memory. Oddly, this can mean that the more often you reconstruct a memory, the less accurate it may become. By Ethan Feng

What happens to matter when it gets extremely hot? And how can this tell us more about the birth of the universe? By Eleanor Lin

Pick a number, any number. Now ask yourself: How "round," or easy to work with, is that number? Could you add, subtract, multiply, and divide it relatively painlessly, and all in your head? By Hannah Prensky

With the rapid progression of climate change, scientists envision two different versions of the future. In the first, humans adopt sustainable, eco-friendly technologies to promote living in a green, flourishing environment. In the second, we don’t tackle climate change and pollution aggressively enough and suffer in a desolate dust bowl, like the Earth depicted in Wall-E or Interstellar. Interestingly, based on new theories proposed by microbiologists, both versions of the future may depend almost entirely on the health of the soil. Seeing Your Doctor Anywhere, Anytime: The Effects of Telehealth on Healthcare and COVID-193/24/2021 By Elaine Zhu

After almost a whole year into quarantine and the pandemic, many of us continue to stay indoors and avoid going outside unless absolutely necessary. However, for some people, especially those with pressing illnesses that need monitoring, going to the doctor’s office is a must. Changes in the traditional method of visiting the doctor’s office are needed to accommodate for these unexpected times in order to reduce transmission to medical staff and patients. Some physicians have turned to a new way to stay connected and engaged with their patients: telehealth. By Jimmy Liu

Have you ever had a sneaking suspicion that the way you perceive what you see is nothing like the next person? Well, that might just be the case—if you can see what you perceive at all. A condition called aphantasia makes one unable to visualize mental images, making those affected by it essentially blind in the mind. By Charlie Bonkowsky

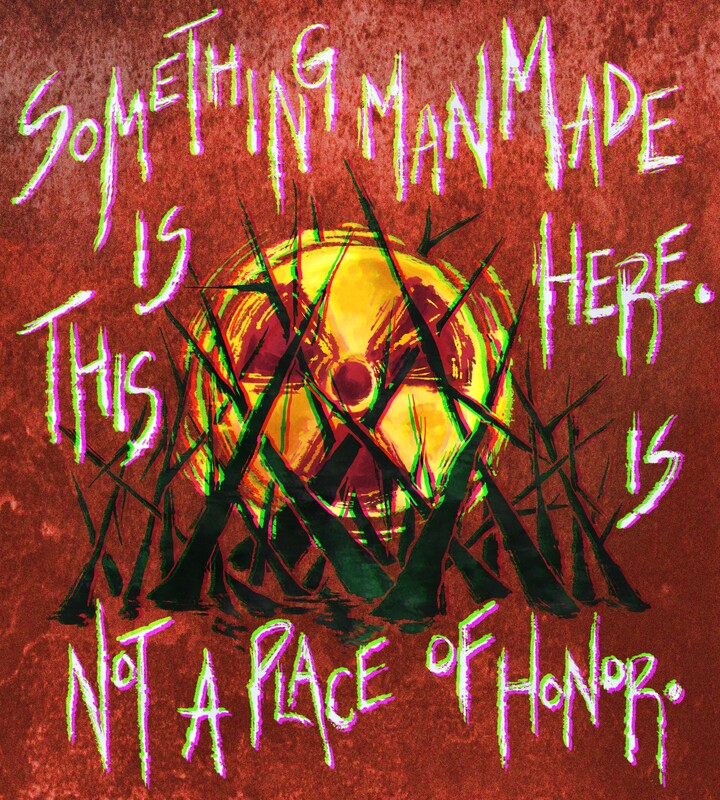

What will happen in 10,000 years? What will the Earth look like? What will human civilization look like? By Eleanor Lin

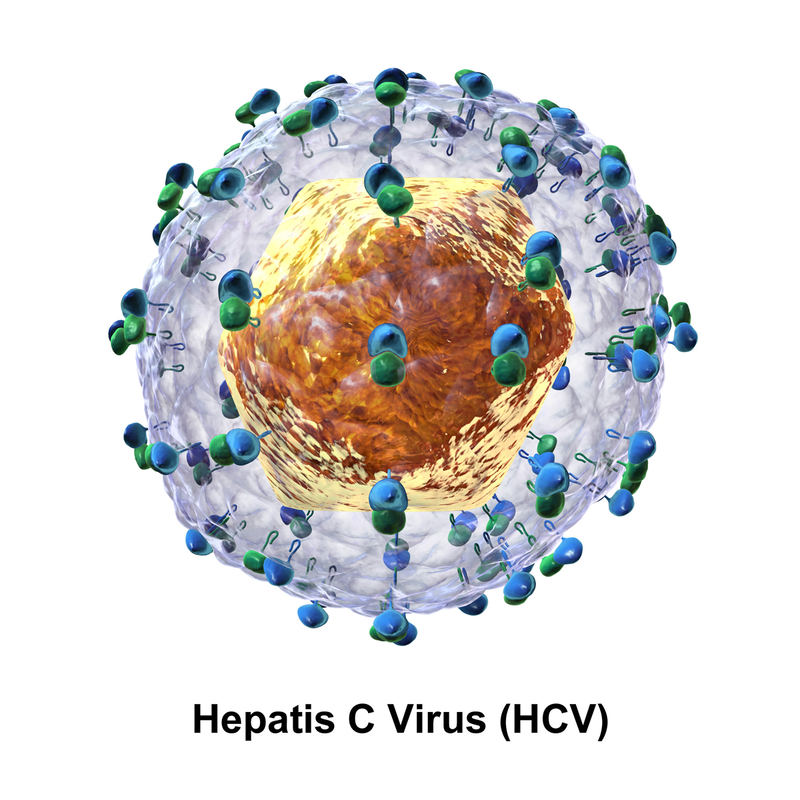

Today, thanks to mandatory screenings, people are able to safely receive life-saving blood transfusions to replenish blood loss from traumatic injuries. That was not the case in 1667: the first documented blood transfusions to humans went horribly wrong, resulting in two deaths. Unbeknownst to physicians at the time, it is extremely dangerous to transfer blood from one person to another without checking to make sure that their blood types match, and that the donor's blood does not carry any pathogens (i.e. harmful particles such as viruses). If the donor's blood type does not match the recipient's, it could trigger a fatal immune response in the recipient; if pathogens are present in the donor's blood, they could create serious disease. |

Categories

All

Archives

April 2024

|