|

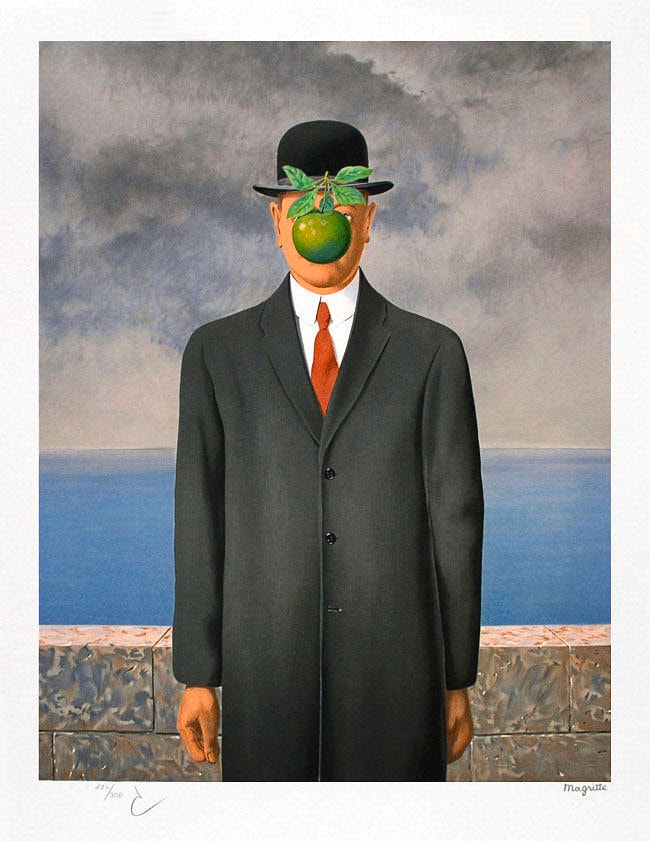

By Jimmy Liu Have you ever had a sneaking suspicion that the way you perceive what you see is nothing like the next person? Well, that might just be the case—if you can see what you perceive at all. A condition called aphantasia makes one unable to visualize mental images, making those affected by it essentially blind in the mind. Your first reaction might be that of doubt: is there empirical evidence to back this up, or is it a conception created by failed artists and students struggling to read Dante? Although most studies that have investigated this condition have relied on subjective experience in the form of questionnaires, the original study from which “aphantasia” got its name has proven that aphantasia has a real neural basis. In 2003, a 65-year-old man came to Dr. Adam Zemen with a unique request: he wanted his imagination back. When undergoing an earlier heart procedure, the patient—later called “MX”—suffered a minor stroke. He found afterwards that he was no longer able to conjure up images in his mind. Having never heard of anything like this condition, Dr. Zemen was fascinated. After administering questionnaires that assessed the ability to produce imagery, the team proceeded to functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) analysis. By using blood oxygenation level as a proxy for localized neural activity, the team monitored MX’s brain when he was asked to visualize the memory of a person, place, or object. Compared to the controls, MX’s frontal lobe, which is responsible for decision-making and reasoning, was more active. His occipital lobe, which contains the visual cortex, showed very little activity. Instead of conjuring up visualizations in his head, it seemed that MX was rationalizing what he ought to picture. When the team published their results in 2010, many people reached out to Dr. Zemen. They said that MX’s condition was exactly what it was like for them, except that their condition had always been part of their lives. Since then, further studies have estimated that about two percent of the population have aphantasia—a much higher number than anyone might have guessed. Many have expressed relief and empowerment in being able to put a name to a prominent feature of their lives where they would be met with confusion before. Celebrities with aphantasia also came forward—including Ed Catmull, a co-founder of Pixar and Blake Ross, a co-founder of Firefox—further calling attention to the previously unknown condition. Though the news of this condition is nothing new for some “aphants,” others are completely oblivious to their condition before hearing about it. Ashley Xu, a junior at Williams College, first learned that she had aphantasia when her friend mentioned the condition to her in passing. She was confused: what does it mean to visualize something in “the mind’s eye”? When her friend asked her to visualize an apple, she responded, “in my mind, it was black, but I knew that there was a little leaf, there was a brown stem, it was a red apple, but I just couldn’t see it.” For people like me who can conjure up images in their minds, questions naturally arise: how do aphants go about their daily lives, and how do they recognize anything, if they do not know what the object, place, or person looks like beforehand? Surprisingly, aphantasia has little practical effect, which is why some only discover their condition after it has been named. When MX was asked whether grass or pine is a darker shade of green, he correctly discerned “pine.” When asked how he did it, he insisted that he used no visual imagery—“I just know it.” One would think that aphantasia, which vastly affects our internal worlds, would be more well-recognized than it is. One reason this is apparently not the case may be the inadequacy of language to represent experience, which is prevalent in Jacque Derrida’s philosophy. Abstract ideas, like beauty and truth, are clearly not perceived the same way, but what is less obvious is that the same inconsistency holds true for seemingly more concrete details, like a dress’ particular shade of cream. How does one know if how one sees, smells, and hears the same object as another, even if we have a common word for it? The discovery of aphantasia shows how the use of language (“picture it in your mind’s eye,” for example) can overlook differences in our spectacles, each tinted a different shade. There is perhaps no objective reality out there, but that is not such a bad thing. With time, scientific research will uncover different aspects of our subjective realities.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Categories

All

Archives

April 2024

|