|

By Ian Cohn

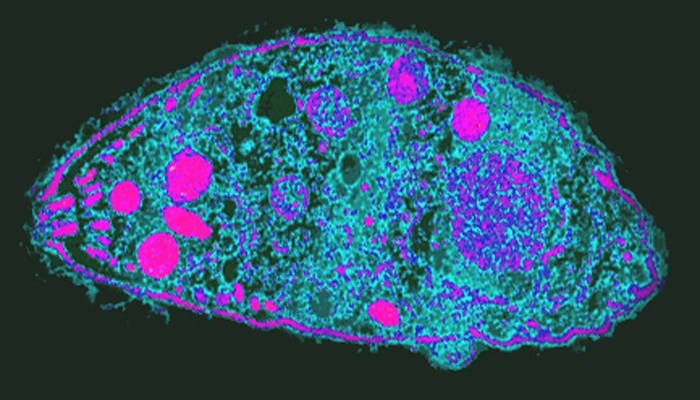

Edited by Bryce Harlan To many, the idea of mind control seems like science fiction. The small parasite Toxoplasma gondii, however, known to alter behavior in rats, may possess the ability to change behavior in humans as well, giving it mind-altering capabilities usually reserved for super-advanced futuristic humans. T. gondii is a unicellular parasite that sexually reproduces in the intestines of cats, but can survive in any warm-blooded mammal. It is thought to spread through cat feces, and has long been known to cause unusual effects in its hosts. In 2000, research team Berdoy, Webster, and Macdonald showed that T. gondii in fact changes the behavior in rats. More specifically, it eliminates rats’ inherent fear of cats, and may even make them more attracted to them. The scientists were able to show this by spraying an area of an enclosed environment with cat urine, which would normally cause rats to avoid that area. T. gondii-infected rats, however, lost their aversion to that area of the cage, and even showed a preference for the areas in their environment which retained the odor of cat urine. It has been suggested that this effect, i.e., reducing their fear of and encouraging their attraction to cats, encourages T. gondii’s own transmission. Thus, T. gondii may spread in two ways: cats ingesting other cats’ feces, and cats ingesting parasite-infected prey—such as rats. Thus, by reducing rats’ fear of cats, T. gondii encourages its own spread via this second route. Once inside its mammalian host, T. gondii resides in various organs surrounded by small, thin-walled cysts (tough protective capsules). These cysts commonly occur in the brain of the host, and in the case of rats, often occur in the amygdala–the part of the brain associated with fear and anxiety. Because of this, aside from subtle behavioral changes, the rats remain fairly asymptomatic when infected with T. gondii. This phenomenon is not unique to rats–in humans, toxoplasmosis—being infected with T. gondii—rarely causes observable symptoms; or at least, it isn’t thought to. Nonetheless, an estimated one-third of the world’s population is thought to carry toxoplasma infection, which presumably spreads through poor hygiene and contact with cat feces. Hence a better understanding of the parasite’s effect on human beings is warranted. The prevalence of toxoplasmosis and the known effect of T. gondii on rats have led scientists to speculate a variety of effects that the parasite may have on humans. Some have even gone so far as to claim that the “crazy cat-lady” phenotype is a result of behavioral changes induced by T. gondii to encourage its own transmission. While this may seem like complete speculation, research has recently suggested that T. gondii may be responsible for one-fifth of the schizophrenia cases in the world. Indeed, in areas where toxoplasmosis is more prevalent, so too is schizophrenia. In one 2007 study, researchers found that the number of antibodies to T. gondii, which would presumably be produced by the immune system in response to the foreign infection as are all antibodies, tended to be higher in schizophrenic patients than non-schizophrenic patients. In another study, patients who developed schizophrenia were found to have a higher amount of T. gondii antibodies in blood samples taken before their diagnosis. Nevertheless, correlation does not imply causation, and whether the parasite can actually cause schizophrenia, or whether it can cause other behavioral changes as it does in rats in humans too remains to be determined. While the causal mechanisms by which T. gondii induces schizophrenia in humans, or whether it does at all, remain largely unknown, this model of infection provides an important new perspective on mental illness pathology. While mental illnesses are often thought to either be genetic or induced by a traumatic experience, T. gondii, while not the only example, may provide evidence that mental illness can perhaps be as infectious as many other illness are. If this is the case, prevention and treatment of mental disorders may need to take on a whole new personality. If the links between T. gondii and schizophrenia are verified, perhaps one day there will even be a schizophrenia “vaccine.” In addition, the ever-dissolving strict separation between diseases of the mind and diseases of the body may be further diminished if certain mental illnesses are shown to be caused by infectious agents. A newfound understanding of specific mental illnesses as infectious diseases may help reduce the stigmas associated with talking and sharing experiences about a broader set of mental illness. For now, we can continue to explore the role T. gondii has on human behavior and use it as a model by which to investigate the pathologies of other mental illnesses.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Categories

All

Archives

April 2024

|