|

Written By Tiago Palmisano

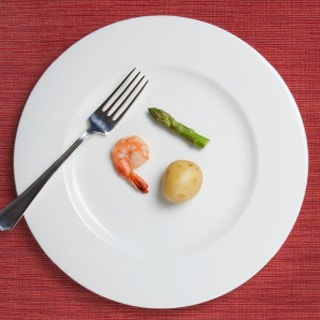

Edited By Bryce Harlan Paleodiet, Atkins diet, vegan diet, raw food diet – new and interesting food management plans such as these constantly pervade the realm of fitness culture. Weight Watchers International, for example, has capitalized on this obsession by providing specific combinations of food in exchange for money. Some of these “discovered” diets seem extreme or outright ridiculous, and a few of them are actually backed by research studies. And one such counter-intuitive diet, based around the concept of caloric restriction, is slowly gaining credibility in the scientific community. The idea of caloric restriction (CR) is pretty much self-explanatory. As put by a 2014 article published in Nature, CR is “Reduced calorie intake without malnutrition.” In other words, caloric restriction involves eating a fraction (usually between 50 and 80 percent) of the normal amount of food consumed. An important stipulation is “without malnutrition,” which means that all of the essential organic compounds must be included. For a human, this is the equivalent of having a trained nutritionist design a meal plan in which all of the necessary nutrients and vitamins are provided in a very small number of calories. This is not the same as just skipping desert. Caloric restriction involves eating less than most people, even less than the typical healthy or lean individual. For example, imagine skipping every fourth meal and you can begin to imagine the reality of reducing caloric intake by twenty-five percent. A diet in which an organism approaches starvation is certainty counter-intuitive, and is indeed dangerous if done incorrectly. Therefore, the positive effects of caloric restriction are still not widely accepted, and its efficacy is currently the subject of research. Previous studies have found that CR increases lifespan and slows the onset of age-associated pathologies in organisms such as mice, fish, and worms. Remarkably, these animals were shown to live longer by simply eating a fraction of their normal food intake (without maturation, of course). The mechanism by which CR increases lifespan is unknown, but one potential reason is that consuming fewer calories reduces metabolism. A reduction in metabolism is accompanied by a reduction in reactive oxygen species (ROS), which cause biological damage and are thought to play a role in the aging process. As one study in The American Journal of Clinical Nutritionwrote, CR increases lifespan by slowing the “rate of living.” Although a decent amount of research exists for CR in lower organisms (such as mice), only a few studies have been published that examine its effect in higher mammals. In 2009, a study published in Sciencemagazine offered the results of a twenty-year study of caloric restriction in rhesus monkeys, a close ancestor of humans. At the end of this experiment, eighty percent of the monkeys on the CR diet were still alive, compared with only fifty percent of the normally fed animals. Additionally, the monkeys on the CR diet developed, on average, less cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and cancer. While such a result seems to suggest that caloric restriction would increase the lifespan of humans, there is still much scientific work that needs to happen before we can safely bring this diet outside of the laboratory. Other similar studies on CR in rhesus monkeys have not been as conclusive, and ethical dilemmas make it difficult to gather data for long-term CR in humans. However, some brave participants have tested the effects of significantly cutting down their food intake, albeit on a much shorter time scale. The National Institutes of Health released an article this September about a clinical trial in which healthy individuals curtailed their caloric intake by approximately twelve percent over a two-year period. The results were generally positive, with a decrease in risk factors for diabetes and heart disease and an increase in good cholesterol (HDL). Despite being counter-intuitive, the CR diet has started to leak into popular culture. A reporter for New York Magazine experimented with caloric restriction for two months in 2007 and detailed the experience in a feature appropriately titled “The Fast Supper.” There is even an international Caloric Restriction Society, which seeks to spread information of the benefits and guidelines of a CR diet. However, the scientific evidence for the effects of CR in humans is nowhere near airtight. We should wait for better and more substantial data before CR is endorsed as an option for a healthy lifestyle. For now, there are too many unknowns to justify a lifelong commitment to a potentially dangerous diet. Until science has caught up, it’s probably a good idea to stick to Weight Watchers.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Categories

All

Archives

April 2024

|