|

Author Alexander Bernstein

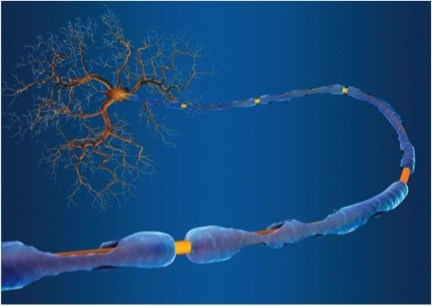

Editor Arianna Winchester Simply described as an autoimmune disease in which the body’s own defense mechanisms attack and degrade the protective myelin sheaths that cover axons in the nervous system, Multiple Sclerosis (MS) is estimated to effect some 250,000 to 350,000 people in the United States alone. The debilitating symptoms of the disorder include numbness and weakness in the limbs, loss of vision, body tremors, dizziness, finally building up to complete nervous system failure and death. Currently, despite how many people are affected by MS and a recent surge in donations towards MS research, there exists nothing even remotely close to a cure. At present, after a diagnosis is given to a patient, the only thing medical professionals can offer is symptom management. Further, there is still no complete understanding of what causes the disease. The only current medical knowledge claims that the disease is marked by an autoimmune response damaging the body’s own nervous system. Recent research has been seeking to reach a better understanding of what causes the disease. A presentation at the 2014 MS Boston Meeting suggested an interesting link between MS and the gut. It has previously been established that as much as 80 percent of the human immune system is at work in the gut, all as part of a complicated symbiotic relationship in which bacteria, fungi, and various single celled organisms contribute to the overall microbiome in the human body. A shift away from this delicate balance can cause a bevy of disorders like rheumatoid arthritis or diabetes. Regarding this connection between MS and the microbiome, a new study from the Brigham and Women’s Hospital is suggesting that single celled organism known as methanobrevibacteriaceae, present primarily in the gut, may play a role in the development of MS. Previous links between the MS and the microbiome have been found in US and Japanese studies. These studies have quantitatively demonstrated stark contrasts between the microbiomes of MS patients and the microbiomes of their healthy counterparts. Now, the recent study from the Brigham and Women’s Hospital reports that their baceriaceae, which is associated with activation of the immune system, is significantly augmented in the gut of MS patients. One exciting consequence of this work is that its conclusions may enable us to affect, or even drastically lower the onset of nerve diseases such as MS by modifying and establishing diets. Sushrut Jangi, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center physician and co-author of the study, emphasizes the potential importance of external factors on the microbiome and thereby autoimmune diseases, saying, “People who emigrate from non-Western countries, including India, where MS rates are low, consequently develop a high risk of disease in the U.S. One idea to explain this is that the biome may shift from an Indian biome to an American biome.” Further support for this connection arises from the effectiveness of the MS drug glatiramer acetate. In MS patients, the drug has proven to have the capacity to suppress excessive immune activity, thereby alleviating the effects of the disorder, though medical professionals do not know exactly how. A coalition of US research centers known as the MS Microbiome Consortium tested the drug in relation to the microbiome to try to elucidate a connection between the two body systems. After administering the MS drug, they saw a distinct change in gut flora populations. Although the role of inherent genetic differences in immune system function cannot be ruled out, the connection that has been demonstrated between MS and the microbiome holds great promise to eventually lead to external stimuli guidelines for how to minimize onset of the disease.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Categories

All

Archives

April 2024

|