|

By Alex Bernstein

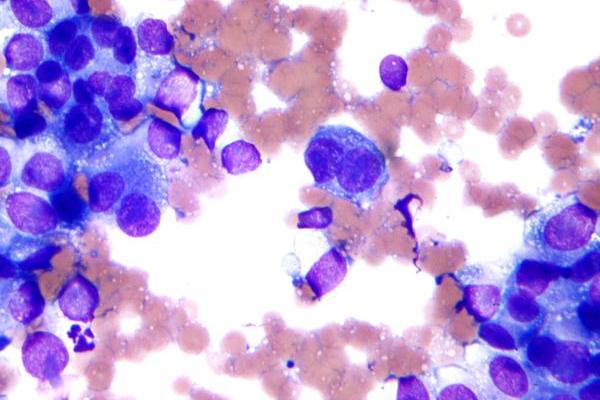

Until quite recently, oncologists, despite all of the progress that has been made in the field, could at best make educated guesses when asked about survival chances by patients. When Cassandra Caton, an 18-year-old tragically diagnosed with a large melanoma growth inside her eye, asked, “Am I going to die, is my baby going to have a mommy in 5 years?” doctors were only able to make a prediction based on the shape and size of the tumor. Now, however, Caton has a much better option. A new genetic test, pioneered by J. William Harbour of Washington University, could provide her with a remarkably accurate prognosis. Identifying which one of the two chief types of genetic patterns the patient’s melanoma falls into, this novel test is able to place the patient’s cancer into either Class 1 or Class 2. The former represents the milder tumor, which is essentially cured through surgery, while the latter is indicative of a more aggressive malignancy, which claims the lives of about 70 to 80% of patients within five years. Remarkably, the test is even detailed enough to predict where future potential cancer growth might appear during metastasis (the spread of cancer), accurately predicting that the liver is the organ to be watched. So far only available for ocular melanoma, the test represents great progress in the oncology community. Dr. Michael Birrer, specialist in ovarian cancer at the Massachusetts General Hospital, is more than enthusiastic about the procedure, calling it “unbelievably impressive,” going as far as saying, “I would die to have something like that in ovarian cancer.” Similar prediction procedures are already in the works for other cancers, such as those of the blood and bones. However, as is usually the case with new science, ethical issues are raised. People often have trouble finding out if they have the genetic makeup for certain incurable disorders such as early Alzheimer’s or Huntington’s disease. The same can be said for such a cancer test, which will either essentially assure patients of their survival, or signify almost certain death. Some doctors even opt to not offer the test, suggesting that there aren’t many benefits it can provide in terms of treatment. A melanoma researcher at Massachusetts General, Dr. Keith Flaherty explains that although the test is able to separate people into two prognostic groups, “There is no treatment yet that will alter the natural history of the disease.” Yet despite such concerns, most doctors do believe in the test, and as Dr. Harbour notes, the overwhelming majority of patients ask for it. When dealing with something like cancer, people want to be as informed as possible. Harbour explains that he gives patients “as much information as [he thinks] they can handle.” Dr. Harbor continues to express his support for the test as he suggests that a Class 2 identification can provide the doctor with the opportunity to better manage the melanoma by knowing what to expect and what tests to run. Regardless, the procedure signifies great progress and hints at just how important genetic testing will be to the future successes in this field. As for Ms. Caton, despite the large size of her tumor, the cancer turned out to be Class 1, a very positive diagnosis that would not be possible without the test.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Categories

All

Archives

April 2024

|