|

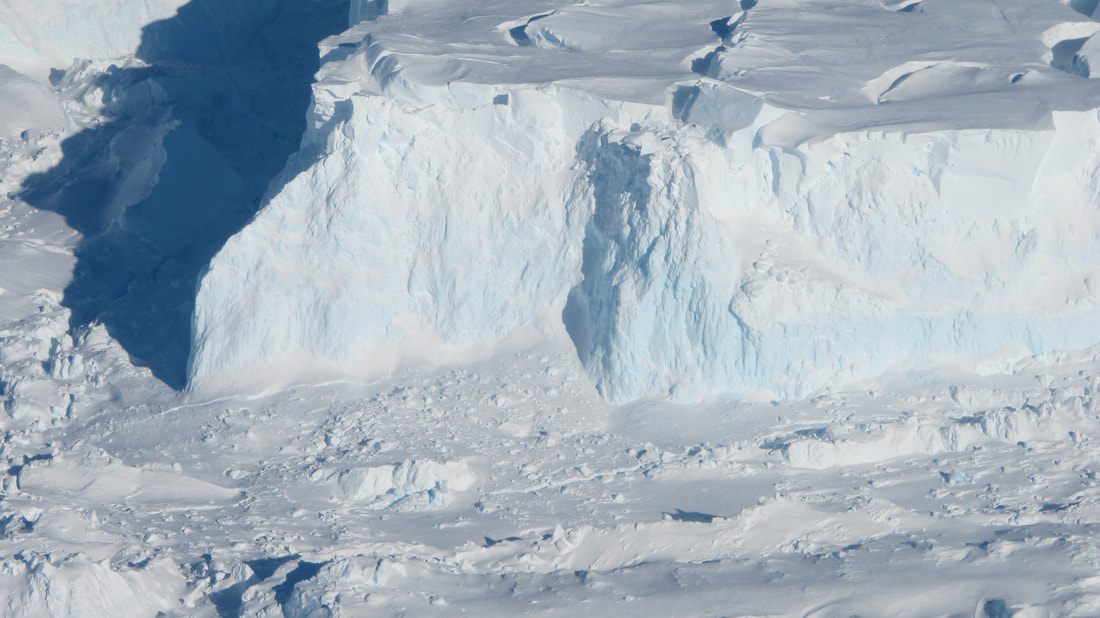

By Jenna Everard Covering around 10 percent of the Earth’s surface, glaciers are an important resource for humans. Not only do their movements provide glacial till, which are sediments derived from glacial erosion that provide fertile soil, but glaciers also store 69 percent of the world’s freshwater supply. Although glaciers’ fluctuating masses have allowed scientists to begin quantifying the impacts of anthropogenic climate change, there is still much we do not know about these fascinating, massive bodies of ice. Studying glaciers can be extremely hazardous: in a process called iceberg calving, chunks of ice can break off from the edge of a glacier, causing unpredictable dangers such as falling ice masses and turbulent waves. This danger is even greater when conducting scientific studies about climate change and sea level rise—in order to investigate how ocean warming causes ice sheets to melt, it is essential to observe the physical points at which the ocean meets the ice sheets. In other words, once must go directly beneath the towering cliffs! Luckily, innovative and safe ways to do just that are being devised. As announced late last year, researchers from Rutgers University have been deploying robotic kayaks to survey the LeConte Glacier in Alaska, where dangerous conditions prevent in-person data collection. Programmed to get as close to the towering cliffs as possible, these kayaks measure how much glacial freshwater melts into the ocean from beneath the glaciers, a phenomenon known as “ambient meltwater intrusions.” Due to the prevalent hazards, ambient melting hasn’t been well studied, and its incorporation into models that simulate glacial melting has only been estimated. These traditional models assume that the impact of ambient melting is minor in comparison to the impact of discharge-driven melting (melting that occurs at the surface through processes such as the aforementioned iceberg calving). However, based on new robotic data, researchers have challenged the previous ambient plume melting rates of 0.05 vertical meters per day: their new findings indicate a rate of about 5 vertical meters per day. This is 100 times higher than anticipated. The development of new technologies such as autonomous kayaks couldn’t have come at a better time. Already, automated robots are being called for their next mission—Thwaites glacier, or Antarctica’s so-called “Doomsday Glacier,” located on the West Antarctic Ice Sheet. This glacier is larger than the state of Florida, with a colossal 75-mile front of ice. As a result of the Thwaites glacier’s historic trends of high ice loss, at approximately 50 billion tons per year, satellites detected a massive cavity, equating to the loss of about 14 billion tons of ice, beneath the Thwaites glacier in February 2020. This further contributes to the unstable configuration of the glacier, bringing the possibility of a glacial collapse closer to reality. While such a collapse would inevitably raise sea levels, and impact 40% of the world’s population who live near coasts, researchers assert that this isn’t the only concern. Even small amounts of glacial melting have the potential to bring about much larger changes in the global climate. Our oceans play a major role in regulating the Earth’s climate, distributing heat through vital processes such as the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC), a flow which brings warm water from the Gulf of Mexico to Europe. As glaciers melt, this circulation is slowing down, causing colder winters and warmer summers in the North Atlantic. These changing temperatures disturb nutrient cycles in the ocean and, in turn, disrupt the biological functions of various marine organisms. They also initiate a positive feedback mechanism, in which raised temperatures cause further glacial melting, which slows the AMOC further, which then raises temperatures even more. If we are to address these concerns, it is necessary to further understand the processes that are causing these glaciers to melt. Whether that be through the use of robotic kayaks or squads of sensor-equipped seals, there is no doubt that modern technological advances and creative ingenuities will lead the way. Although the Thwaites Glacier’s Twitter Page ominuously warns that it’s “COMING SOON to sea level near you,” and although such changes may be inevitable, by furthering our understanding of underwater melting, we can reassess the impacts of sea-level rise and refine our strategies for responding to and minimizing the harm of this imminent future.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Categories

All

Archives

April 2024

|