|

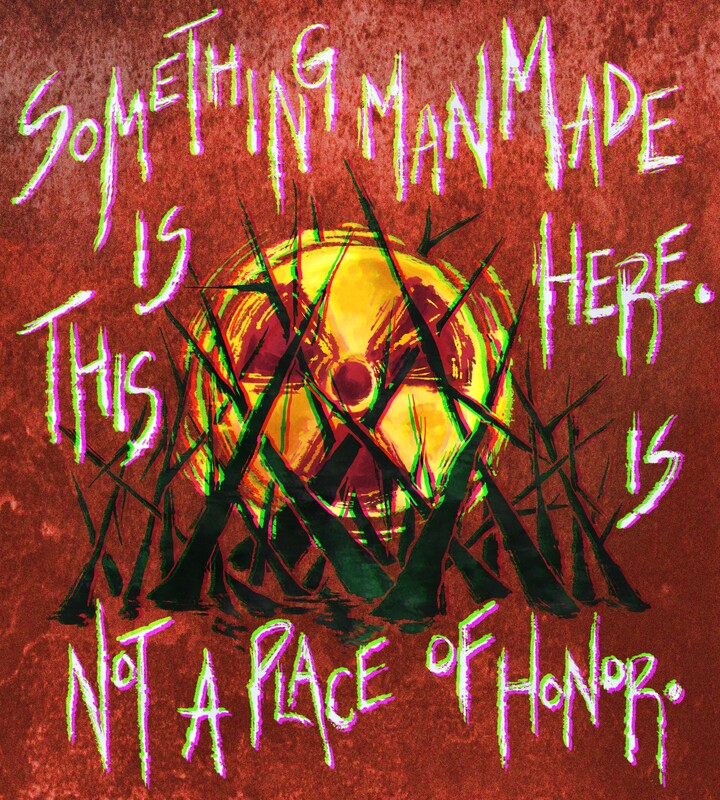

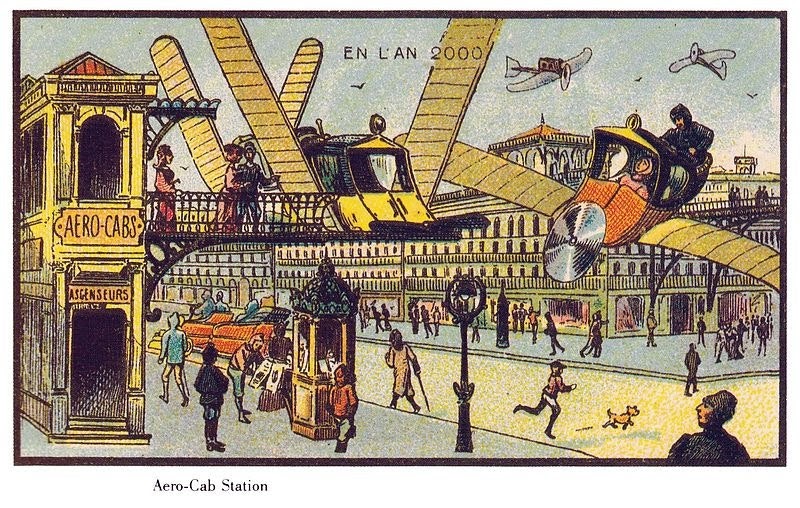

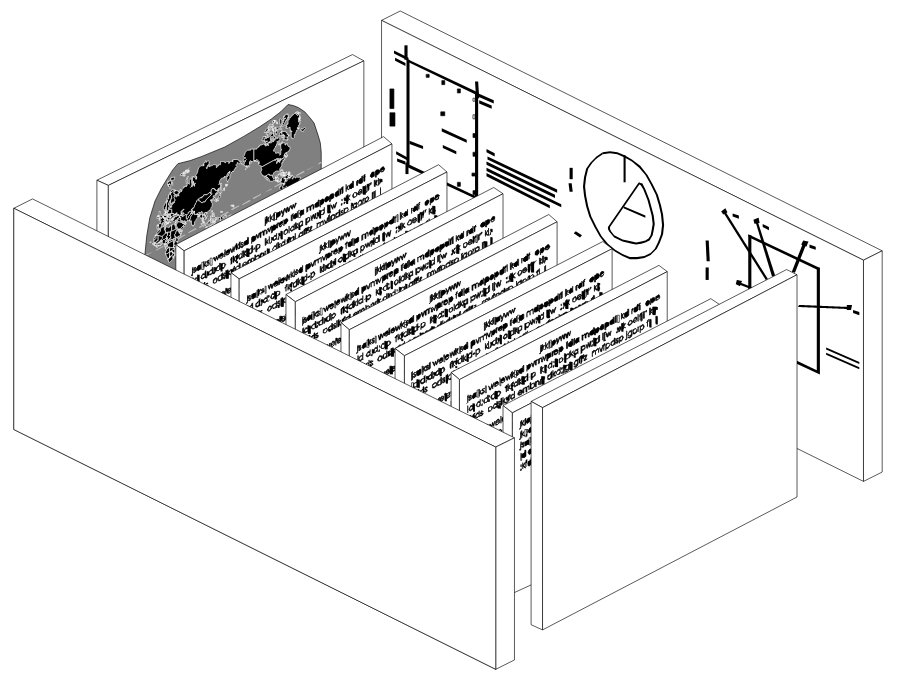

By Charlie Bonkowsky What will happen in 10,000 years? What will the Earth look like? What will human civilization look like? Nobody knows. Few of us could have predicted what the year 2020 would look like, and our predictions for the far future are even less accurate, constrained by our own visions of technology and human interactions with it. At the turn of the 20th century, French artists attempted to depict what the year 2000 would look like—their visions were rife with propellers, brass, and zeppelins. While fascinating, they reflect nothing of what our present looks like now: Yet we do know one thing about the future: our nuclear waste will still be here. Nuclear testing and power plants create lethally radioactive waste, which must be buried to prevent exposure for at least 10,000 years, the minimum time for it to drop below the threshold for hazardous radiation. The sites marked out for excavation are some of the most geologically stable in the world, hundreds or thousands of feet underground, and—once completed—should require no maintenance or supervision. The biggest threat to these sites will not be environmental. It will be future humans who may have no knowledge of the fatal radiation that these sealed rooms contain. How do we tell them of a danger which they won’t be able to see or sense? And how do we make sure they take it seriously? Humans have a knack for doing things we’re explicitly told not to: as the British author Terry Pratchett wrote, “If you put a large switch in some cave somewhere, with a sign on it saying 'End-of-the-World Switch. PLEASE DO NOT TOUCH,' the paint wouldn't even have time to dry.” The first problem is that almost any form of language is guaranteed to change to a degree such that it will be virtually unrecognizable by the inhabitants of the future. Take the opening of Beowulf in its original Old English form: Hwæt. We Gardena in geardagum, þeodcyninga, þrym gefrunon, hu ða æþelingas ellen fremedon. Translated into a more recognizable form, it reads: (LO, praise of the prowess of people-kings of spear-armed Danes, in days long sped, we have heard, and what honor the athelings won!) Only a few scholars can parse the text without translation, and only a thousand years have passed since it was published. There are no records of the languages that existed 10,000 years ago—Sumerian, one of the oldest we know of, is only half that age, and many more languages have been lost to time. For many scholars and scientists, this problem is nearly intractable. Language is a requirement to communicate complex ideas, especially of the type necessary for long-term nuclear waste sites. Pictograms and images, while more resilient against linguistic drift, can be ambiguous in their meaning. For example, when people were asked what the biohazardous waste symbol meant to them, some said it indicated that they should dig down—exactly the opposite of what was intended. In 1993, the Sandia National Laboratory, looking to address this problem, stated in a report that any message or information conveyed about a nuclear waste site should be ordered in increasing complexity: Level I: Rudimentary Information: "Something manmade is here," Level II: Cautionary Information: "Something manmade is here and it is dangerous” Level III: Basic Information: Tells the what, why, when, where, who, and how Level IV: Complex Information: Highly detailed, written records, tables, figures, graphs, maps, and diagrams. Levels III and IV require written information to exist. Given that we have no idea how future political or cultural boundaries will change, most proposals have suggested writing this information in dozens of languages with space for future societies to add their own translations. Below is a proposed image of such an “information center” at the Waste Isolation Pilot Plant in New Mexico: an open, blocky structure made of stone designed to draw attention to itself by having the air whistle through it. But the ideas for how to convey Level I and Level II messages are much more diverse, given that they are meant to work around the ideas of language—no matter what happens to human society, or how much knowledge is lost in the intervening years. Though most of the specific details would be contained in the information center, the Sandia report also intended that the entirety of the nuclear waste site would communicate the following message: This place is a message...and part of a system of messages...pay attention to it! Sending this message was important to us. We considered ourselves to be a powerful culture. This place is not a place of honor...no highly esteemed deed is commemorated here ...nothing valued is here. What is here was dangerous and repulsive to us. This message is a warning about danger. The danger is in a particular location.. . it increases towards a center.. .the center of danger is here...of a particular size and shape, and below us. The danger is still present, in your time, as it was in ours. The danger is to the body, and it can kill. The form of the danger is an emanation of energy. The danger is unleashed only if you substantially disturb this place physically. This place is best shunned and left uninhabited. Architecture The Sandia report makes the following recommendations on the architecture of the site:

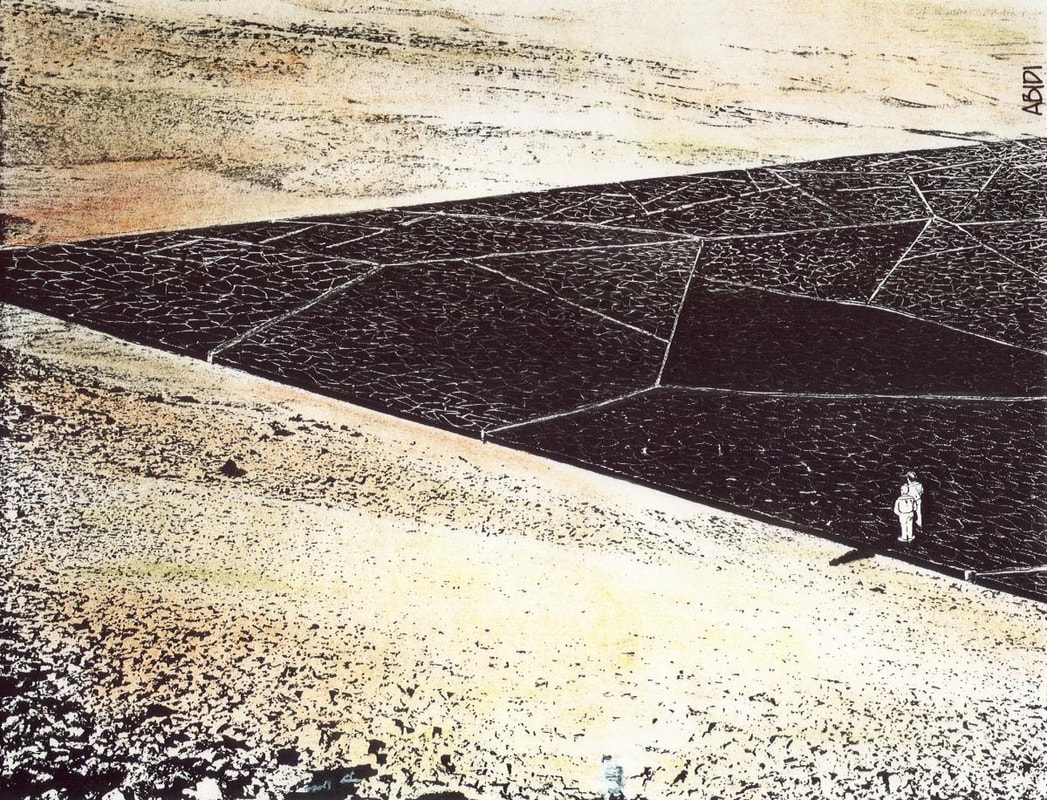

With those restrictions in mind, several artists and architects have proposed their own visions of hostile architecture. Michael Brill, who worked with the Sandia team, drew several concepts. Each and every design was dark, hostile, and utterly forbidding. Cultural Memory Other social scientists have proposed embedding the warnings of these sites into our long-term culture. Thomas Sebok proposed the creation of an Atomic Priesthood at a 1981 Department of Energy conference, which would preserve the knowledge and danger of the atomic sites through rituals and myths. After all, religions are some of humanity’s longest-lasting institutions and have been able to successfully preserve messages for millennia. However, such a proposal raises both ethical questions of creating a priestly caste as well as practical questions for how to prevent the religion from changing over time. There are thousands of Christian denominations across the world today, each with a slightly different set of beliefs—who’s to say that the same wouldn’t happen to such an atomic priesthood? At the same conference where Sebok first considered the atomic priesthood, others offered even stranger ideas. A Polish science-fiction writer, Stanislaw Lem (and, independently, the physicist Phillipp Sonntag) proposed the creation of an artificial satellite with warnings engraved upon it. In space, the messages wouldn’t be subject to earthly degradation and would be similarly safe from any future-human’s attempts to tamper with the warning. But it runs into the same problem as all other messages: would the people of the future be able to read, or understand, what the satellite is warning them about? Two other proposals instead considered changing nature itself to act as a warning. Lem proposed that plants and vegetation could be genetically modified into record-keepers of a type, encoding details about the nuclear site in the DNA of the plants. In addition, a pair of French scientists offered up the idea of adapting cats’ fur to change color in the presence of radiation. So long as our cohabitation with cats continues (and there’s no reason to think it wouldn’t), warnings when a cat’s fur changes color could become embedded into long-term cultural memory. Currently, no government has plans to create a new religion, launch an artificial moon, or genetically engineer our cats and local vegetation. Most intend to do what the U.S. government implemented for the above-mentioned Waste Isolation Pilot Plant in New Mexico—place signs in multiple languages on scattered black obelisks, trusting that there will still be people in the far future who can decipher the written text. Maybe there will be—maybe the visions of societal collapse and large-scale knowledge loss are nothing more than pessimism. But governments are bad at predicting the future, just as humans are. We don’t know what will survive over hundreds of generations, what relics of the present will be left in the future—all we can do today is shoulder the responsibility we’ve created for ourselves, the thousands of tons of nuclear waste that must be disposed of somewhere, and hope that whatever we do will be enough.

1 Comment

Oma

3/20/2021 01:36:29 pm

Surely scientists will eventually find a way to neutralize the waste. Maybe you will be the one to discover something. I’m convinced it will eventually happen.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

Categories

All

Archives

April 2024

|