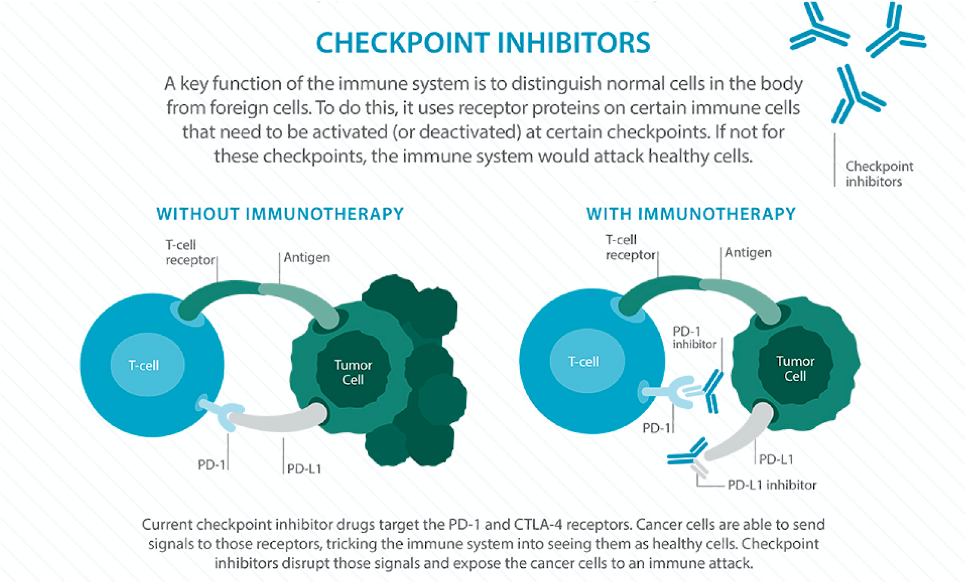

By Clare Nimura Why can’t your immune system fight cancer the same way it fights a common cold? The immune system is supposed to recognize the bad things in your body, eradicate them, and let you go on with your life, healthy. Why does the body’s defense system fail when it comes to cancer? This month, the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine was awarded to James P. Allison and Tasuku Honjo for their work on immunotherapy. These two doctors independently discovered the importance of checkpoints (specifically CTLA-4 and PD-1) in manipulating the immune system and revolutionized the field of cancer treatment. Before we can appreciate how monumental these discoveries are, we need to take a step back: how does the immune system work? What even is a checkpoint? The immune system is composed of cells, tissues, and organs that coordinate to attack antigens, or any foreign or dangerous substance in the body. Some immune cells have the job of identifying antigens and calling for a larger immune response. These cells tag the antigen with small proteins called antibodies, which act as a “destroy me” tag recognizable by other immune cells. Each type of antibody latches onto a specific antigen. Despite this elaborate defense system, cancer has found a way to slip past the immune system’s careful watch. How does it do it? Essentially, cancer cells have the ability to flip the “on/off switch” of immune cells, hiding themselves from being recognized as harmful. These “on/off switches” are proteins on the immune cell surface called checkpoints. Many cancer cells produce complementary proteins on their surfaces that bind to these checkpoints, which send the signal to the immune cell saying, “I’m harmless!” and prevent any immune response. This is a problem: if the immune system cannot recognize the cancerous cell, it cannot do anything to destroy it. What if there was a way to train your body’s immune system to recognize cancerous cells and give it the strength to overcome the disease? Well, there is a way: immunotherapy. Immunotherapy is an exhilarating frontier of cancer treatment, voted “Breakthrough of the Year” by Science Magazine in 2013. It harnesses the body’s own immune system, super-charging it to battle cancer. There are three main categories of cancer immunotherapy: adoptive cell transfer, monoclonal antibodies and checkpoint inhibition. Drs. Allison and Honjo won the Nobel Prize for their work specifically on checkpoint inhibition. Let’s take a closer look at how checkpoint inhibition works. When cancer cells “turn off” immune cells, they apply the brakes to the immune system. Checkpoint inhibition releases these brakes, allowing the immune cells to recognize the cancer cells as harmful and to function at full capacity. A new class of drugs called “checkpoint inhibitors” acts by binding to—and effectively disabling—the checkpoints on the immune cells or the proteins on the surfaces of the cancer cells. If these proteins cannot interact with each other, then the immune cells cannot be “turned off.” There is now a whole range of drugs that block different checkpoints, allowing the immune system to function without receiving inhibitory signals from cancer cells. Basically, checkpoint inhibitors destroy the cancer cells’ hiding technique so the immune system can do its job. Immunotherapy is an exciting frontier of medicine that is emerging into mainstream treatment. So far, it is FDA approved for melanoma, lung cancer, head and neck cancer, Hodgkin lymphoma, kidney cancer, bladder cancer and Merkel cell carcinoma. So far it has been most effective in melanoma and non-small cell lung cancer, with some clinical trials showing almost doubled overall survival. Other clinical trials are even exploring the prospect of using immunotherapy in other diseases like Alzheimer’s and multiple sclerosis. However, like any other treatment, immunotherapy is not a miracle solution and does not come without drawbacks. Patients often experience flu-like symptoms or inflammation as side effects—consequences of an overactive immune system—and the treatment is not universally effective. Different types of immunotherapy also work better for different cases. For example, adoptive cell transfer and monoclonal antibodies involve more complex procedures but provide more specificity in treatment, whereas checkpoint inhibitors use a simpler mechanism and boost the immune system generally. Endless questions still surround immunotherapy: Does it work best alone or in combination with other cancer therapies like chemotherapy, radiation, and surgery? Why doesn’t immunotherapy work for every patient? What are the long term effects of immunotherapy? Due to these and other uncertainties, immunotherapy is typically a “second-line” treatment, introduced after patients have progressed on the traditional treatments of chemotherapy, radiation, and surgery. While there is still much to discover in the field of immunotherapy, the recognition of Dr. Allison’s and Dr. Honjo’s work marks the beginning of a new era of cancer treatment, one where our very own immune system becomes a valuable weapon. Maybe someday we will be able to treat cancer the same way we treat a common cold.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Categories

All

Archives

April 2024

|