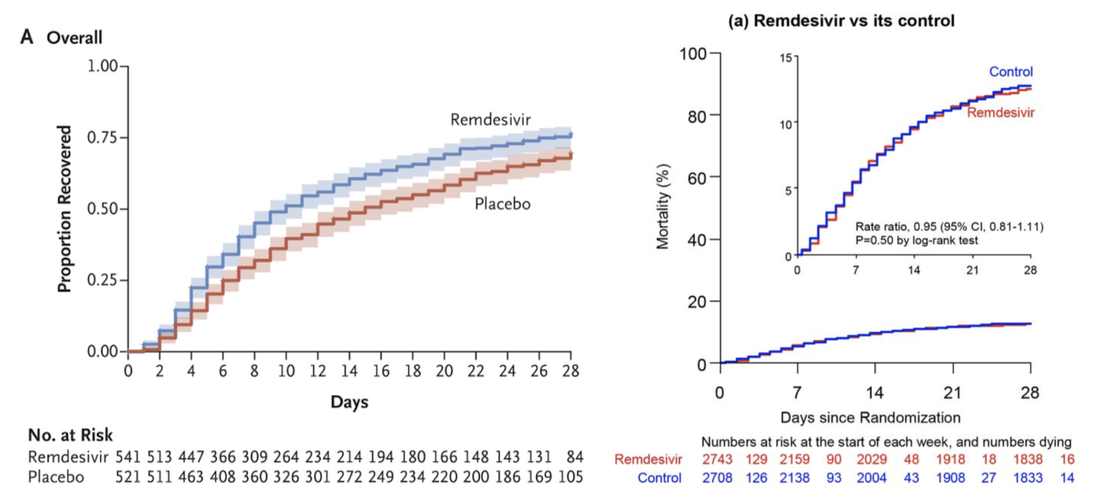

In world’s largest clinical trial for current COVID-19 treatments, drugs appear to have no effect12/18/2020 By Hannah Prensky On October 15, the World Health Organization published a manuscript (not yet peer-reviewed) studying the efficacy of several drugs that have been repurposed to treat severe cases of COVID-19. During a public health emergency, the medical community can turn to previously approved drugs as a way to treat patients in a timely manner. The study demonstrated that Hydroxychloroquine, Remdesivir, Lopinavir/Ritonavir, and Interferon-β1a treatments have little to no effect on mortality or length of hospital stay with regard to COVID-19. These results indicate that the only current treatment options for patients hospitalized with COVID-19 are not effective at combating the virus. The study comprised data from 30 countries, 405 hospitals, and 11,266 patients collected over six months--a stunning achievement by the international scientific community. The group of researchers, known as the “Solidarity Trial Consortium,” hailed from all six inhabited continents and constituted the world’s largest randomized control trial on current treatment options used for COVID-19. Since studies with larger sample sizes generally yield more precise results, these results could be more reliable than those collected from smaller trials. Over the course of the study, 1,253 participant lives were sadly lost to COVID-19. These patients came from both cohorts—either receiving a drug or a placebo—which allowed doctors to report the mortality rate of each drug tested as compared to that of its control. Concerningly, during some trials, a larger share of people on medication died than those in control groups. These results held true across age, severity (“severe” defined as requiring ventilation), and geographic location. Moreover, none of the four drugs significantly reduced the need for a ventilator in patients who were not already on one when the study commenced. By the end of the study, the ratios of patients who began to need ventilators over the course of the study were as follows, presented in drug:control group form: Remdesivir: 1.04, Hydroxychloroquine: 1.13, Lopinavir: 1.04, and Interferon-β1a: 0.995. If it is true that these treatment options for COVID-19 do not work against the virus, how and why did the international medical community start using them on patients? In a study from Wuhan, China, published in Nature in early February 2020, researchers tested several FDA-approved antiviral drugs for use against COVID-19. The results demonstrated that chloroquine and Remdesivir were effective at blocking the coronavirus from entering cells in vitro. Although cell culture does not always mimic what happens in humans, doctors were desperate for treatments at a time when little if anything was known about the coronavirus. In the spring, doctors in China and France reported improvements when treating patients with hydroxychloroquine, a drug similar to chloroquine, coupled with an antibiotic. Notably, these were small samples (62 patients) and were not double-blind randomized control trials, which are the gold standard of medical research. Then, after President Trump started promoting Hydroxychloroquine as a “game-changer” without formal proof, prescriptions for the drug soared like never before. Supply dwindled for people who needed the drug the most to treat Lupus, a serious autoimmune disease. Although a study of almost 400 patients showed that Hydroxychloroquine could actually increase death rates in COVID-19 patients, the president responded to the results by stating that “obviously there have been some very good reports and perhaps this one is not a good report.” The president may have been right about the report not being “good”: it was not a randomized control trial and was never peer-reviewed. However, the results ultimately agreed with the death ratio (treated:placebo) published by the WHO, 1.19. The WHO study also investigated the efficacy of Interferon-β1a, a drug used to treat neuroinflammation in multiple sclerosis. A July randomized control study (n= 42) by researchers in Iran showed no difference between treated and placebo groups in length of hospital stay or time on a ventilator. However, just one week after the Iranian study was published, a clinical trial conducted in the United Kingdom using inhalable Interferon-β1a showed more promising results, though the National Institutes of Health (NIH) indicates that more detail is required before making any conclusions. Furthermore, the type of inhalable Interferon-β1a is not currently available in the United States. Currently, health experts advise against using this drug for treatment against COVID-19. Perhaps the most controversial conclusion raised by this study was that Remdesivir, a broad spectrum antiviral medication produced by the American pharmaceutical giant Gilead, does not affect the mortality or severity of COVID-19. Despite these results from the WHO coming to light on October 15, the FDA granted emergency approval for Remdesivir on October 22. It is important to note that while the United States was not involved in the WHO study, American scientists from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAD) published its own findings on Remdesivir in the New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM) on October 8, which showed significantly more promising results. The controversy arises when analysing NEJM and WHO results side by side: These results, obtained using similar methods, lead to opposing conclusions. On the one hand, the American study by the NEJM shows a clear, significant improvement on COVID-19 recovery rate when using Remdesivir. On the other hand, the worldwide study by the WHO shows absolutely no effect on mortality by the same drug. Which results should we believe, and what do we do when two different reports yield different conclusions? As stated earlier, the scope of the WHO study is unmatched, possibly yielding more reliable results. In the two graphs shown above, the WHO’s study had over five times the number of participants as the NEJM study. The difference in sample size doesn’t invalidate any of the findings alone, but there are other considerations one can use to analyze the trustworthiness of peer-reviewed science, including reading the “conflict of interest statement” that must accompany any peer-reviewed study published in a medical journal. Neither the NEJM nor the WHO study self-reported any conflicts of interest. However, it is intriguing that the NEJM study, the only study showing significant improvements with Remdesivir, was funded in part by Gilead and conducted by a team including Gilead employees. That particular study directly led to the FDA’s emergency use authorization of Remdesivir for COVID-19. The drug is very cheap to produce, costing Gilead $0.93 per treatment day, but was priced by Gilead at $2,340 for a course of treatment, or $3,120 for United States patients with private health insurance. In just two weeks following the publication by the NEJM, Gilead generated nearly $900 million in sales from Remdesivir, with 99.999% constituting pure profit. The question remains: should doctors continue using Remdesivir even though results indicate it doesn’t work against COVID-19? If the NEJM is right and there is any possibility that it can save a life, it could be worth it. However, Americans are paying far too much for a drug that has been proven not to work when, instead, we could be investing that time and money into other, better solutions.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Categories

All

Archives

April 2024

|