|

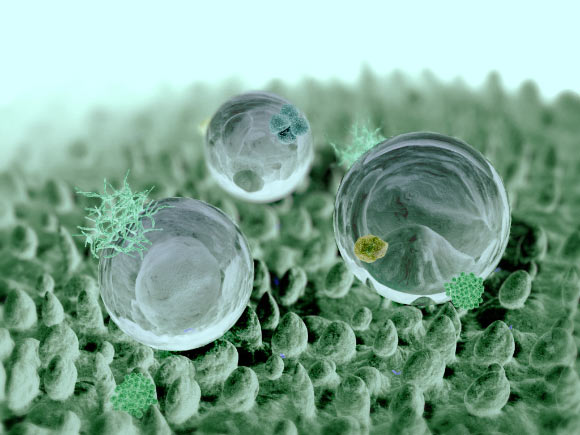

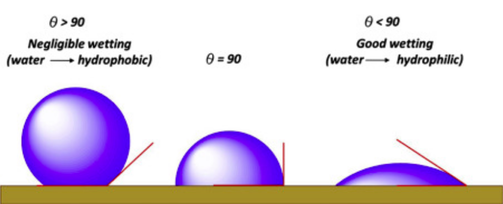

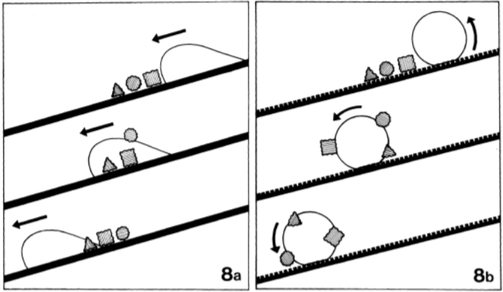

By Boyuan Chen The lotus is associated with the purity of mind and soul in many religions, including Buddhism and Hinduism, for its ability to arise from muddy ponds and yet remain unstained. Even in Latin, the name “lotus” comes from the participle for “washed,” in recognition of its forever-clean appearance. But why is this the case? What is the scientific basis for this fascinating phenomenon? To explain the self-cleansing property of the lotus leaf, it is important to first understand how water wets a surface. Per its technical definition, “wetting” is the thermodynamic process whereby water molecules come into direct contact with a solid surface by replacing its surrounding air molecules. The molecules in the water, solid surface, and air all have differing affinities for one another, which are determined by what is known as surface energy. Surface energy arises from the contact between these different molecules and is dependent on the contact area and the surface properties of all interfaces: the higher the contact area, the higher the surface energy. The process of wetting thus reaches equilibrium when the surface energies of all interfaces have also reached equilibrium and achieved a certain ratio between the water-air contact area and the water-solid contact area is attained. The area dependence of this equilibrium implies that if the “density” of surface area—or the “surface area per surface area”—can somehow be increased, the droplet can attain the necessary equilibrium without needing to cover a large geometric surface. This “density” of surface area is actually simply a measure of the roughness of a solid surface: for the same macroscopic area, a rough surface has much greater surface area than a smooth surface, and thus a greater surface area per surface area. This means that a water droplet can cover enough surface area on a microscopic scale to attain equilibrium while only spreading out over a relatively small macroscopic area. It turns out that the surface of a lotus leaf is a perfect example of a rough surface. Although appearing smooth macroscopically, the surface of a lotus leaf is, in reality, crowded with nano-structures called papillae—tiny bumps grown out from the plant’s epidermal cells. In addition, biological wax crystals secreted from epidermal cells prevent water from sticking onto the leaf’s surface while further increasing the surface area. As a combined result, the surface of lotus leaves becomes extremely difficult to wet, so water droplets can retain their spherical shapes without spreading thin. This spherical shape and the wax-coating on the leaves’ surface means that these droplets have a higher tendency to simply “roll off” the leaves, making it nearly impossible for the water to stick onto the surface. The anti-wetting property of lotus leaves has two consequences: they are difficult to stain and easy to clean. As you may have experienced when driving a newly-washed car down a muddy road, the muddy water splashes everywhere, leaving dry mud caked on the car’s hood once the water evaporates. Now if the car’s surface had the anti-wetting property of a lotus leaf, the splashes would immediately roll off. This means that the muddy contaminant cannot stay on the surface as the water evaporates, thereby preventing the formation of a solid stain. Contact angle, as illustrated, is the angle between the surface and the line that is tangent to the surface of the droplet at point of contact. Even if the contaminant comes from another source—say, dust particles in the air—lotus leaves can still facilitate the cleaning process. When we clean our car after a muddy ride, we usually rely on the pressure of the water stream and the mechanical forces of the brush to wash off the mud stains. In nature, however, the most common clean water source is rain drops, which have neither the pressure nor the mechanical force to remove dust particles on surfaces. Rather, raindrops typically glide slowly and gently across a surface, which does not help to remove tightly-adhering dust particles (of course, tropical storms are a different story). On lotus leaves, however, due to the large contact angle, water droplets tend to literally “roll.” As they roll, they gain a higher rotatory velocity at the interface, allowing them to better “pick up” the dust particles (which adhere to the droplets due to, no surprise, surface energy) rather than simply running over them. This easy-to-clean property of lotus is called self-cleaning. The self-cleaning ability of lotus leaves has inspired scientists to develop materials with a similar surface structure. In fact, most durable water-repellent materials utilize the lotus effect. In one instance, a group of researchers from Europe used laser-cutting to create a lotus-like microstructure on metal, which, when used in food factories, reduces the amount of bacteria that sticks onto the surface, since the liquids that carry the bacteria cannot stay there. This lotus-like structure can also be found within water-repellent cloth, spray and construction materials. With clean surfaces, we just might be able to achieve purity of soul someday, just like the lotus.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Categories

All

Archives

April 2024

|