|

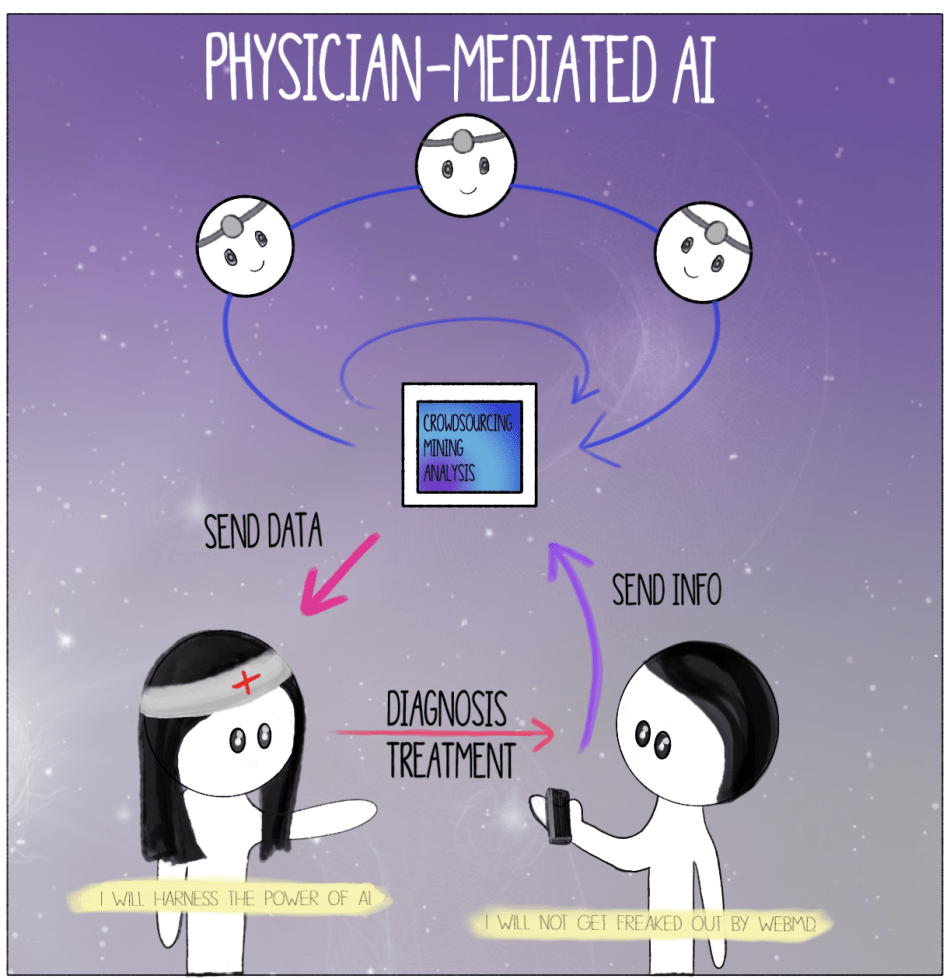

By Ashley Sun and Sirena Khanna It’s time for your annual check-up. As you enter the doctor’s office you are greeted by the receptionist at the door. Just like last year, you begin your visit with a health questionnaire. You’re happy to discover that this time the survey is given to you on a tablet with a Google Form—no more painful scribbling against a crusty clipboard. You start scrolling through the questions. In the last year, were you or anyone in your family admitted for an overnight stay in a hospital? “No.” Have you ever been diagnosed, treated, medicated, and/or monitored for X, Y, and Z diseases? “No, no, and I have no clue what that is.” You mindlessly tap away at the endless survey, which is still as much a bore as the paper version. At the end, you notice an odd question: do you consent to letting artificial intelligence (AI) use information contained in this survey to better assess patient healthcare? You aren’t quite sure what this means, so you walk up to the receptionist whose bright blue eyes flicker on as you approach. “How may I help you?” it automatically asks. You glance at the name tag. “Hey, NurseBot Janet, can you explain this last question to me?” The robot promptly explains that data from these surveys will be privately stored in your Electronic Health Record and will allow AI to help your physician make a personalized plan for your health. Considering that you have nothing to hide about your health, you consent and press “Submit.” Thank you for your response! NurseBot Janet is not far from the future. In fact, engineers in Japan have alreadydesigned robots like nurse bear and Paroto care for elderly patients by conducting a range of activities, from lifting them off beds to engaging in simple conversation. The potential for artificial intelligence (AI) in the healthcare industry is as vast as your imagination. Dozens of start-ups around the world have created a buzzing field of medical AI. As of now, AI companies have focused on data storage (Google Deepmind Health), crowdsourcing data for research (Atomwise, IBM WatsonPaths), predictive analytics (CloudMedX Health), hospital management (Olive), medical imaging (Arterys, VoxelCloud, Infervision), and personalized care (Bio Beats, CareSkore, Freenome, Zephyr Health). AI has proven to be much better than humans at mining medical records, assessing the success of different treatment options, and analyzing medical scans. With the future of medical AI like Nursebot Janet on the rise, is the healthcare industry going to experience an AI apocalypse,as foretold by Elon Musk? The AI apocalypse may have already begun in your own smartphone. The current market for health-related applications consists of around a quarter million health apps, each of which are relatively sophisticated. These apps often extend far beyond basic diagnostic searches, and include the use of personalized information such as photographs of skin lesions for the detection of melanoma. The sheer detail and convenience that these apps provide have driven consumer demand to new levels. According to a report by Accenture, health app downloads and wearable technology usage have tripled and quadrupled, respectively, in the past four years. The expectations for these tools to deliver high-quality information and care has increased accordingly, as user experience has become a major priority in such apps. With these developments, new issues are emerging concerning the information provided through AI. Studies have been conducted regarding the diagnostic accuracy of apps that focus on melanomas, in particular, and have raised serious questions about the quality of medical information for cancer risks. There are tangible legal and ethical consequencesregarding life-threatening mistakes and how responsibility should be assigned with AI-generated diagnoses. Questions of trust are also being considered, specifically concerning the privacy and security of personal, medical informationbeing stored by private companies. In dealing with these issues, the FDAhas, nevertheless, determined that apps used for diagnosis, treatment, or prevention of disease pose a low risk to the public; as a result, there is minimal regulation at odds with the obvious need for management on health advice that may not always be evidence-based. Ultimately, the main bioethical issues of individualized care, provided through AI-based health apps, are those of accountability, confidentiality, trust, accuracy, and comprehensiveness. Who is accountable for the information provided to the patient? Can you trust an AI company to give you the best health advice? In order to avoid these particular bioethical issues, it may be best for AI health apps to be made specifically for physician use rather than widespread commercial use. Say goodbye to NurseBot Janet. Welcome your living, breathing, human physician. Although smartphone apps may be a great way to empower the patient and give them autonomy over their health, physician-mediated AI use would avoid a multitude of legal and bioethical issues associated with health apps, such as those of regulation and accuracy. How should AI be used as a tool by physicians to personalize patient healthcare? When patients interact with AI apps that are also connected to healthcare providers, their data and a machine-generated diagnosis can be sent to a responsible physician, who would then make the final decisions regarding actual medical care. When many of these patient-AI-physician relationships occur at the same time, the machine learning aspects of AI in apps would augment their decision-making accuracy, which would be repeatedly confirmed by medical professionals, as well. This system would mimic organizations like Human Dxand Figure 1, which are crowdsourcing platforms that rely on solutions proposed by a range of healthcare professionals to solve ambiguous cases. A greater reliance on the opinions of multiple physicians would mitigate inaccurate or overly cautious AI-based recommendations and would aggregate symptoms to create reliable banks of data for future diagnoses. The combined knowledge of physicians and AI will curate more healthcare optionsthat are personalized for the patient. It will also maintain the emotional and humanizing aspect of care in the direct physician-patient relationship. With this paradigm, the physician can ensure personalized healthcare while avoiding the slippery slope of patients self-diagnosing with misinformation. The physician’s involvement also guarantees a level of confidentiality and legal responsibility that currently unregulated health apps do not afford. For example, technologies like Apple’s single-lead ECG featureon their Apple Watch allows the user to print PDFs of their results to share with their physician. AI companies should model their product development under this physician-mediated model, like ADA does, to ensure the most bioethical product. For those skeptical of AI healthcare, rest assured that human doctors will not be replaced by robot clinicians anytime soon. Instead of NurseBot Janet, it’s more probable that you encounter NurseApp Janet, an online smartphone app that stores biometric information and surveys your health for your real-life physician to check each year. Luckily, you agreed to Janet collecting your health information, so the next time you come for your check-up, you won’t need to answer the boring and generic patient questionnaire. Through the app, AI has gathered the answers to these questions, while your healthcare provider has consulted with a crowd-sourced sharing platform to come up with accurate and comprehensive healthcare advice for your mysterious disease. On your next visit to the doctor’s office, you’re glad to see that NurseBot Janet has been replaced by—you take a closer look at the nametag—Janet, a human this time. For now, the AI apocalypse can be averted by keeping humans in charge of your healthcare.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Categories

All

Archives

April 2024

|