|

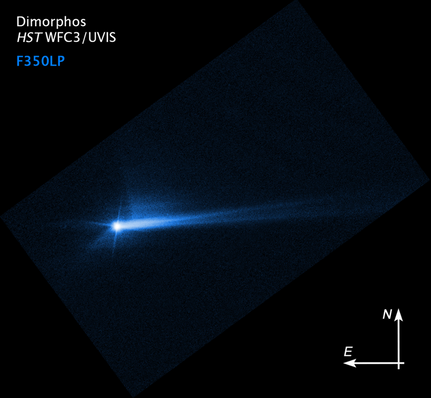

By Charles Bonkowsky Instead of watching the Super Bowl, you could have been watching a meteor slam into the Earth’s atmosphere. On the night of February 12, astronomer and geology professor Krisztian Sarneczky spotted the asteroid from the Konkoly Observatory in Hungary, and realized that its trajectory was likely bringing it onto a collision course with Earth. Following the usual protocol, he reported it to the Minor Planets Center (MPC), a database that alerts other astronomers about potentially interesting Solar System objects. Once the entry was published, telescopes across Europe and the ESA confirmed his predictions—and alerted people to point their cameras at the sky for the spectacular fireball. The asteroid, designated 2023 CX1, is the seventh ever small asteroid to be spotted before impact—most meteors are caught only when they become an incandescent streak across the sky. Each of those asteroids’ discoveries has followed the same path. One astronomer—like David Rankin, who spotted the asteroid 2022 WJ1 that burned up over Canada in November—spots something interesting and reports it to the MPC, after which a host of other telescopes pin down its trajectory and collision course. Many amateur astronomers are part of this work, simply because it doesn’t necessarily take a high-powered observatory to spot these asteroids; you just need to be looking in the right place at the right time. The Northeast Kansas Amateur Astronomers’ League, for instance, was instrumental in collecting data on 2022 WJ1, and they’ve discovered over 600 asteroids to date. Fortunately, none of these asteroids have posted any threat to Earth. But there are bigger threats out there, marauding asteroids miles in diameter that could wipe out all life on Earth if they hit. How are we searching for them? Both NASA, through its Planetary Defense Coordination Office, and the ESA, through its Near-Earth Objects Coordination Centre, have dedicated programs searching the sky for asteroids. They’ve found thousands of asteroids, which are evaluated by the level of risk they might pose to the planet: once an asteroid is observed, its orbit is projected hundreds of years into the future to see if there’s any chance it might strike Earth. The good news? They haven’t found any yet. None of the asteroids in NASA or the ESA’s database have any significant risk of impacting the Earth in the next century. The bad news? They haven’t found all of them yet. Population estimates suggest that there are probably about 1000 asteroids greater than a kilometer in diameter which will pass close to Earth and as many as ten or twenty thousand asteroids greater than 100 meters in diameter that could pose a risk of impact. While most of the truly devastating asteroids in the first category have been found and cataloged, there are still many mid-size asteroids which haven’t yet been discovered. At that size, asteroids wouldn’t necessarily cause an extinction-level event, but they’d still be deadly. Meteors carry tremendous amounts of energy, and even small ones—like the Chelyabinsk meteor which burned up over Russia in 2013, and which was a scant 18 meters in diameter—caused over a thousand injuries among people on the ground. Of course, telescopes are frequently adding to the number of discovered asteroids. NASA’s Asteroid Terrestrial-impact Last Alert System (ATLAS) is a network of telescopes that, by the addition in 2022 of two Southern-Hemisphere telescopes, can now scan the entire dark sky every 24 hours to search for asteroids. And NASA is moving forward on a space telescope, the Near-Earth Object Surveyor, which would have greater capabilities to discover hazardous asteroids than any Earth-based telescope. By being located in space, the telescope could find Near-Earth Objects (NEOs) which approach from the direction of the Sun, and the telescope would ultimately aim to discover 90% of all these mid-sized objects within a decade of being launched. Finding them is the first half of the equation—we can’t stop an asteroid if we don’t know it’s coming. But it’s not worth much either to see an asteroid coming without being able to stop it. That’s where NASA’s DART mission comes in. In September 2022, the agency intentionally crashed a probe into an asteroid to test how much they could change its trajectory: a test-fire, in essence, of a system to protect Earth. Early results show that the probe measurably changed the orbit of the asteroid, not just from its own impact but also from the tons of rock and dust launched into space, and NASA is still studying it to determine the magnitude of the momentum change and determine what kind of an impact might be necessary for larger asteroids. NASA imagery of the rock ejected from the surface of the asteroid after the impact of the DART mission.

Development of deflection technology is still ongoing, and our telescopes are still scanning the sky for new asteroids. But as NASA administrator Bill Nelson has said, we’ll “be ready for whatever the universe throws at us.”

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Categories

All

Archives

April 2024

|