|

By Tiago Palmisano

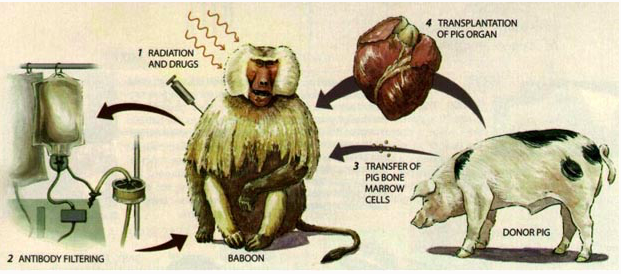

Edited by Bryce Harlan Xenotransplantation. The first time I heard this word I assumed it was something from a sci-fi show. Technology akin to the faster-than-light hyperdrive or the gravitational tractor beam, perhaps. Little did I know that xenotransplantation is not only very real, but also on the frontier of medicine. But enough introductions, I’ll get to the point. Xenotransplantation refers to any procedure in which the tissues or cells of one species are transplanted into another. For instance, the brain of a dog into a cat or (much more realistically) the use of pig skin on a burn patient. But what is the use of xenotransplantation? After all, we seem to be proficient at transplanting organs between humans. Well, the importance of developing this technique stems from the lack of available human organs for the overabundance of people in need of a transplant. At the time I am writing this article 121,177 people in the U.S are waiting for a lifesaving organ donation, according to the Department of Health and Human Services. That number shrinks considerably if we can figure out a way to safely put the organs of animals into humans. Pigs, in particular, are the focus of current xenotransplantation research due to their high supply and the fact that their anatomy is relatively similar to ours. Imagine if a cardiac surgeon could simply order up a pig heart every time a patient went into heart failure. Amazingly, one team of researchers has taken some considerable steps towards that exact goal. They managed to transplant pig hearts into five baboons, and the primates survived for on average 298 days. The remarkable aspect of this experiment is not that the pig hearts were able to effectively pump blood in a baboon body. Rather, the difficult part is preventing the recipient from rejecting the porcine organ. Rejection occurs when the immune system of the host recognizes the new tissue as a foreign and initiates an attack, damaging the transplant and rendering it useless. Organ rejection is a problem even between humans, so the task of getting one species to accept the tissue from another species only complicates the issue. In this study, published at the beginning of April, the researchers used some clever techniques to increase the chance that the baboons would accept the hearts. First they genetically modified the pigs, decreasing the susceptibility of porcine tissues to immune response. Then, once the xenotransplant was complete the baboons were given a drug regimen to help regulate their immune system. Using this strategy, one of the primates was able to live with a pig heart for over two and a half years. This provides substantial evidence that long-term survival of a heart xenotransplant is possible, and the time may be soon approaching when actual xenotransplant surgeons are in hospitals throughout the world. While baboons were used here to serve as approximations for humans, the use of porcine anatomy in humans is not a new idea. The bioartifical liver device (BAL) uses pig liver cells and functions as a temporary dialysis machine for patients with acute liver failure. In this way, the pig liver cells either help the human liver recover or keep the patient alive until a transplant becomes available. Additionally, pig brain cells (neurons) have been used in humans with Parkinson’s disease and Huntington’s disease. It seems as though scientists are slowly finding ways to make the pieces fit. Although the idea of pig parts in human bodies may be off-putting to some, xenotransplants have the potential to make the organ waiting list a thing of the past. And that’s an idea that everyone can enjoy.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Categories

All

Archives

April 2024

|