|

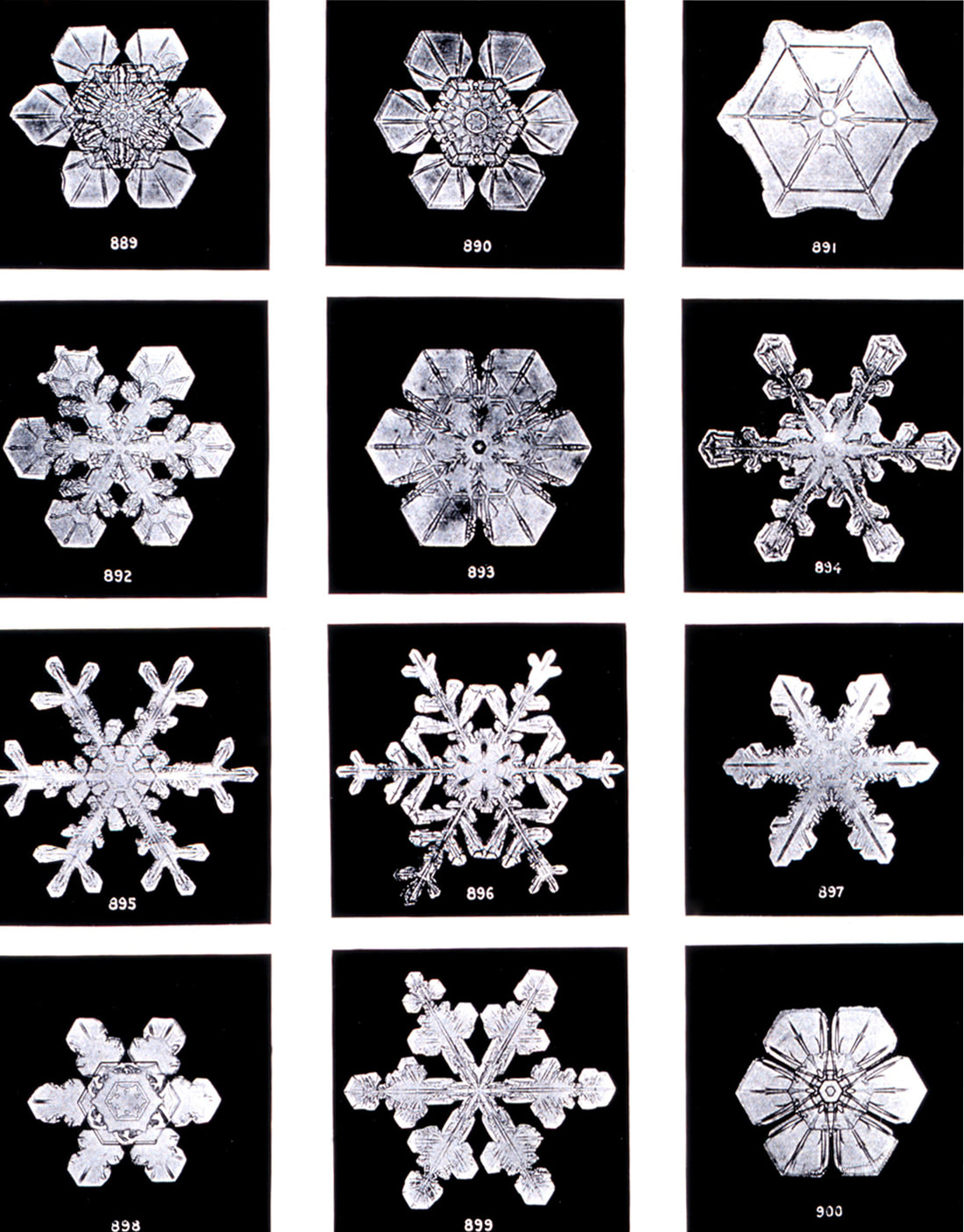

By Elifsu Gencer The joy I feel when I spot a perfect little snowflake on my coat sleeve is truly unmatched. Having been taught that every snowflake is unique, I marvel at the level of detail I can see with my bare eyes on something so small in size. I can’t help but think, though, that it does kind of look like every other snowflake that I’ve examined. How do we know that each snowflake is actually unique? And what does “unique” really mean? The notion that no two snowflakes are alike was introduced by Wilson Bentley in his paper A Study of Snow Crystals, published in 1898. Instead of “snowflakes,” Bentley used the term “snow crystals” to clarify his take on the difference between the two. While a snow crystal is strictly a single crystal of ice, snowflakes may represent a single snow crystal or a “cluster” of snow crystals. Bentley’s fascination with nature, especially the structure of snowflakes, started during his childhood while he lived on his family farm in Vermont, where annual snowfall reached 120 inches. After being gifted a microscope for his fifteenth birthday, Bentley attempted to capture the structure of snowflakes by inspecting them at the microscopic level. Noting the difficulty in studying the structures given that they “ speedily disappeared,” he turned his attention to successfully developing a method in photographing snowflakes. Bentley cleverly attached a camera to his microscope, and after collecting snowflakes on black velvet, he photographed the snowflakes on pre-chilled glass plates outdoors to prolong the integrity of the snowflakes. After many failed attempts, he successfully photographed his first snowflake in January 1885 at just 20 years old. Bentley eventually accumulated an archive of over 5,000 photographs over the course of his life. His research garnered nationwide interest and slides of his snowflake photographs were sold across the United States. Additionally, jewelers began to copy the snowflake designs in their works. The stunning geometric patterns of snowflakes were also incorporated in the design of wallpapers, textiles, and stained glass windows. It is important to note that snowflakes are specifically unique at the molecular level based on their general shape and structure. The current widely accepted classification model includes 35 categories, composed of typical shapes, such as stellar dendrites, as well as unexpected shapes, including 12-sided snowflakes composed of two six-branched crystals with one rotated 30 degrees relative to the other. Snowflakes are formed when water vapor condenses into water droplets on dust particles in the air—aggregates of these suspended water droplets form what we see as clouds. When the clouds begin to cool, the water vapor starts freezing around the dust particles. These heavier droplets fall toward Earth, still growing in size as more water vapor continues to condense and freeze. Ultimately, snowflake formation depends on the temperature and humidity of the air. While the exact reasons for why these conditions result in different shapes is not fully understood, according to Dr. Kenneth G. Libbrecht, a physicist at California Institute of Technology, more intricate snowflake patterns are formed when in humid conditions, while simpler shapes are formed in drier conditions. He also found that snowflakes formed in temperatures below -22 ℃ consisted of simple crystal plates and columns, while those formed in warmer temperatures contained complex branching patterns. Given the impactful influences of factors such as temperature, there are scientists working on developing equations predicting how a snow crystal will grow in certain environmental conditions. Though many did not see the benefits of Bentley’s work at the time, the study of snowflakes can have many applications. For example, Dr. Libbrecht notes that the study of snowflakes can lead to a better understanding of self-assembly, a process in which disarranged molecules form well-defined structures. Self-assembly is especially important in biological systems, such as in the assembly of proteins to form quaternary structures or in the assembly of capsids containing viral DNA. Despite their small size, snowflakes had a profound effect on Bentley and he paved the way to a greater understanding of atmospheric science. We honor him today with Jacqueline Briggs Martin’s Snowflake Bentley, a children’s picture book detailing his life story. Although Bentley tragically died of pneumonia at the age of 66 after walking six miles in a blizzard, his photographs remain a spectacle that we enjoy today.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Categories

All

Archives

April 2024

|