|

By Erik Schiferle

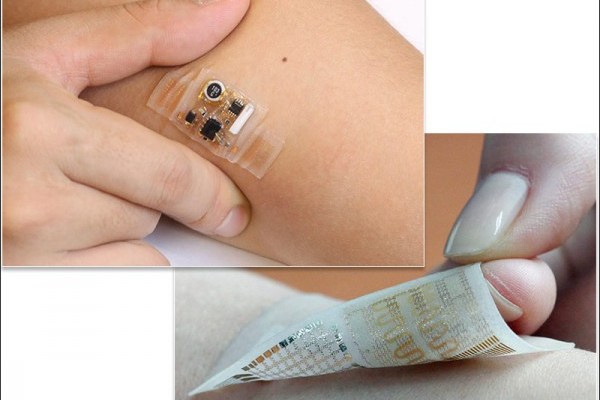

Editor Sophie Park Parkinson’s disease is classified as a degenerative disorder of the central nervous system that results from the deterioration of cells that produce dopamine within the Substantia Nigra–a region within the middle of the brain that is associated with pleasure, addiction, and movement. Symptoms seen within early stages of the disease can include tremors, rigidity, stiffness of the limbs and body, bradykinesia (lethargic movement), and lack of coordination. Symptoms worsen over time to the point where patients may have difficulty with daily activities. Later stages of the disease may also be marked by an increase in depression or emotional instability. Currently, there is no cure for Parkinson’s disease, but various treatments may help alleviate its symptoms. Some patients opt to undergo surgery. Surgery might involve deep brain stimulation, which utilizes electrodes implanted into the brain to provide a high frequency impulse of electricity. This removes some of the brain tissue thought to induce symptoms. However, most patients choose to make changes in lifestyle and begin medication treatment. Medications reduce the symptoms of Parkinson’s disease, but they require patients to take multiple doses throughout the day and may be difficult to keep track of. Consequently, it is not uncommon for patients to miss a few doses. If one were to miss a dose, the patient would unpredictably undergo a range of symptoms that otherwise would have been prevented via medication. In addition, the fact that the medication’s effects only last a few hours (hence the hourly doses) causes patients to experience minor tremors before taking the next dose. Overall, this results in a 24-hour cycle with periods of stability peppered with brief periods of tremors. In response to these problems, the bioengineer Dae-Hyeong Kim and other researchers from Seoul National University in South Korea have developed a flexible patch that automatically administers medications. Made of silicone or plastic onto which circuits are printed, the patch operates using tremor-detecting sensors to monitor medication levels. The sensors utilize a “resistive random-access memory” to keep track of the patient’s tremors over time. The sensor, upon detecting low medication levels via tremors, delivers smaller amounts of medication as needed through silica nanoparticles. As a result, the patient should firstly never miss a required dose of medication, and secondly, patients should not undergo intermittent periods of tremors due to the fact that the medication is administered when biologically necessary. Though exciting to many, this product is still in its early developmental stages. The patch is still built by hand in one of Kim’s university laboratories. Another issue is that flexible batteries and processors do not exist for skin electronics, so the patch relies on an external power source and processor. However, Kim and his associates have proposed that smart phones or watches could be the solution to this problem. Similar to wireless phone chargers seen in stores today, the smart object would charge the patch through inductive charging, which uses an electromagnetic field to transmit energy from one object to the other. The smart object would then also serve as a processor that could send information wirelessly. Kim hopes to have the patch ready for large scale production within the next five years–he even hopes to make this “smart skin” patch a little more fashionable for patients.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Categories

All

Archives

April 2024

|