|

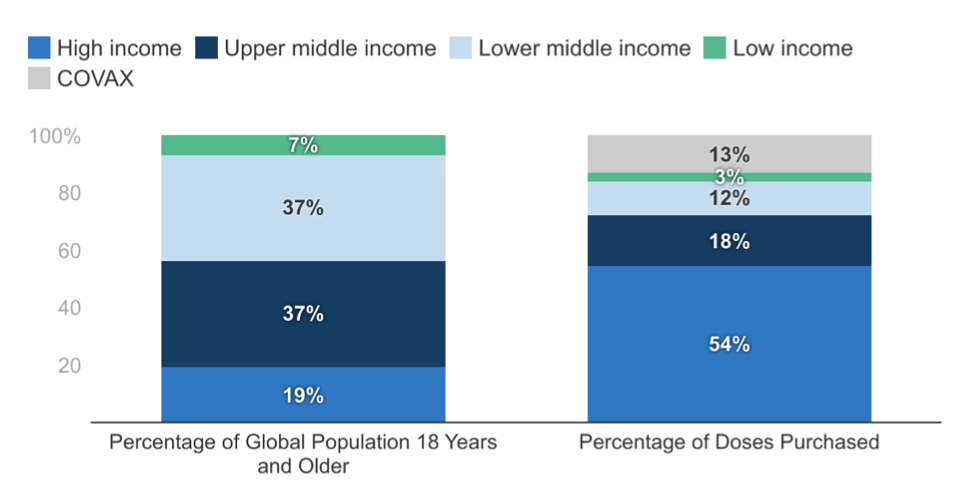

By Aparna Krishnan According to the UK’s Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU), more than 85 poor countries will not have widespread access to COVID-19 vaccines before 2023, if at all. Starting early 2021, vaccines developed by Pfizer (US)-BioNTech (Germany), Moderna (US) and AstraZeneca-Oxford University (UK) have been deployed to treat the SARS-CoV-2 virus — the cause of the COVID-19 pandemic which began in December 2019. Wealthy nations such as the US, UK, and members of the EU have seen a massive vaccine roll-out in just a few months; the US has delivered more than 100 million first doses and the UK, more than 30 million. These developed nations leading the vaccination effort will likely see economic growth starting mid-2021, provided that vaccination continues to accelerate and the public is largely protected from the newly emerging SARS-CoV-2 variants. In fact, The Guardian forecasts that the US will see the most improvement of these nations, “in part due to the planned $1.9 trillion of tax cuts and spending increases that form the centerpiece of [President] Joe Biden’s economic recovery plan.” However, while the countries at the front of the line for vaccines are experiencing gradual economic re-openings, nearly 45% of countries in the world are expected to remain mostly unvaccinated until mid-2022 to 2023. The latest data from the Duke Global Health Innovation Center Launch and Scale Speedometer, which monitors countries’ COVID-19 vaccine purchases, shows that “high-income countries already own more than half of all global doses purchased.” The US is expected to acquire a total of 1.3 billion vaccine doses, more than three times its adult population. In contrast, some middle-income and most low-income countries will rely on COVAX, a WHO initiative aiming to deliver “at least 2 billion doses by the end of the year, including at least 1.3 billion doses to 92 lower income economies.” However, these supplies may be slow to arrive, conditional on whether any production or delivery issues arise in the richer countries. The figure below (last updated March 15, 2021 by the Duke Launch and Scale Speedometer and the World Bank) shows the distribution of vaccine doses purchased by income level compared to its respective proportion in the global adult population:  As the figure demonstrates, despite lower middle income countries having double the percentage of adults than in high income countries (37% and 19%, respectively), high income countries have purchased more than four times the number of doses (12% and 54%, respectively). High-income countries have purchased so many vaccines that they now “own enough doses to vaccinate more than twice their populations while low and middle-income countries (LMICs) can only cover one-third,” also according to the Duke Launch and Scale Speedometer and World Bank. The repercussions of this global inequality are worrisome. One concern is that, without a more equalized vaccine distribution, the goal to immunize approximately 60% to 72% of the world population to attain herd immunity will continue to be delayed. Agathe Demarais, the EIU Global Forecasting Director, also worries that some of these LMICs, after a two-year waiting period, “may well lose the motivation to distribute vaccines, especially if the disease has spread widely or if the associated costs prove too high.” She adds that “many people in poorer countries remain unable to get access to [vaccines against polio or tuberculosis which have been available for decades]. What was termed a ‘novel coronavirus’ only one year ago will be with us for the long term, alongside the many other diseases that have shaped life over the centuries.”

This forecasted loss of motivation among some middle and low-income countries calls for efforts to lessen the disparities between countries’ income levels and their purchased vaccines — mainly via vaccine redistribution. Carlos Del Rio, professor of medicine and global health at Emory University, urges the US to step in and be a leader in the global health arena: “It’s in the interest of the United States to start becoming a vaccine supplier to poorer countries. Other countries [like Russia, China, and India] are seizing opportunities to build goodwill and influence globally, while the United States is still focusing internally on vaccinating its own citizens.” While the US, along with France and the UK, have stated that they will donate any excess doses once their own populations have been fully accounted for, this promise is dependent on the robustness of the vaccines against SARS-CoV-2 and its variants as well as how quickly the doses continue to be manufactured and deployed without error. Another hopeful avenue is the approval of current vaccine candidates in clinical trials. As of April 2021, there are 60 candidates in development, which could potentially boost LMICs’ vaccination rates with increased production of doses. However, leading countries must establish the necessary infrastructure to produce them in addition to the already authorized vaccines, such as Pfizer-BioNTech or Moderna. Still, realizing that helping other nations is in these countries’ own interest and continuing to hold them to these standards should motivate them to address the shocking global health inequalities that have come to light during this pandemic.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Categories

All

Archives

April 2024

|