|

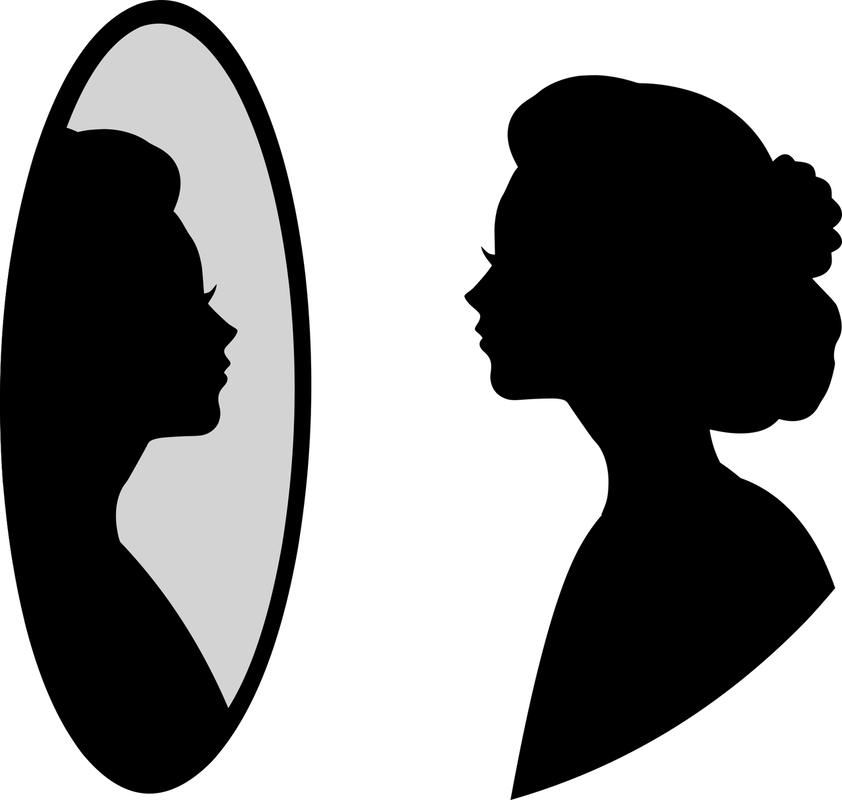

By Joshua Yu A couple of days ago, I was perusing through my Zoom account settings in search for a way to eliminate my awkwardly long middle name from my profile when I stumbled upon a setting that had been automatically selected for me: mirror my video. I thought it was strange that none of the remaining settings had been enabled, so I unchecked the box and logged out, not thinking much about it. When I joined the Zoom call for my chemistry class a few hours later, I was appalled by what I saw. I spent the entire 75-minute lecture staring at what I was expecting to be my reflection—but it did not look like me. The realization that this was how everyone saw me was jarring, to say the least. My preference for a mirrored version of my own face and my disgust for its doppelganger reflection is explained by the “mere-exposure” hypothesis. The term was coined in 1876 by Gustav Fetchner and describes how we tend to like things simply because they are familiar. Since we rarely ever see ourselves in the third person, our minds instinctively characterize our “true” image as bizarre. Part of the reason for which we differentiate between our unmirrored and mirrored appearances is that our faces are more asymmetrical than we would like to believe. Photographer Alex John Beck explored this idea in his project Both Sides Of. Beck published pairs of photographs in which one image is the left side of a model’s face mirrored and the second image is the right side mirrored. The astonishing results highlight the inconsistencies in how we see the world. In various interviews, Beck underscores that the intent of the project was to upend our association of beauty with a perfectly symmetrical face. The phenomenon of the mere-exposure hypothesis has been studied by psychologists in an effort to better understand the human mind. A study conducted in the 1970s presented both true and mirrored pictures of subjects to their families and friends, as well as to the participants themselves. Unsurprisingly, the family and friends preferred the unmirrored images while the participant preferred the mirrored picture. But when asked to justify their preferences, those surveyed claimed that there were lighting or angle differences between the images, when in fact, they were the same picture. The researchers emphasized that the lack of “cogent reasons” for preferring one image over the next indicates that the mirror and true images are nearly indistinguishable. The overwhelming dislike of the unfamiliar image cements the validity of the mere-exposure hypothesis as a natural mechanism for deciding what we “like.” Many front-facing cameras also unmirror your image when you snap a photo. In fact, with selfies specifically, the short distance between our smartphone’s camera and your face can exaggerate your features. A paper published in the Journal of the American Medical Association Facial Plastic Surgery found that selfies taken 12 inches from a subject’s face increased the size of subjects’ nose by nearly 30 percent. Since we usually see ourselves in the mirror from a greater distance, our familiarity with our appearance is reliant on that perception remaining constant. Though currently unproven, this reasoning could also be a contributing factor to the rising acclaim of the selfie-stick. Thankfully, the mere-exposure hypothesis also provides a relatively quick fix to this dilemma: exposure. By simply taking more selfies and keeping your video unmirrored on Zoom, your brain will begin to familiarize itself with the face the rest of the world sees. This hypothesis also extends to everything from food to music tastes to job interviews. So the next time you quickly dismiss something based on an initial impression, remember that your tastes can change over time.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Categories

All

Archives

April 2024

|